Manuel Carrión

1817 Sevilla – 24 July 1876 Milano

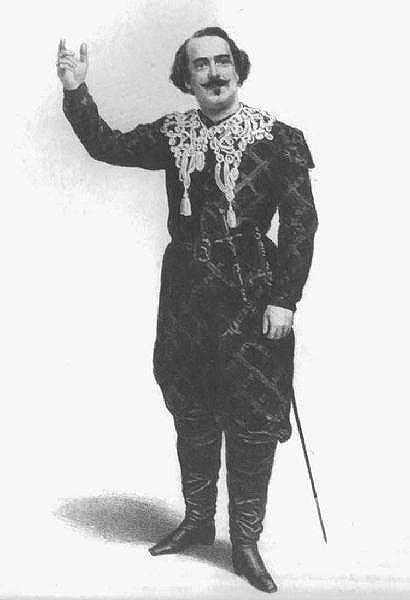

Manuel Carrión as Edgardo, Victoria Theater Berlin 1859

Manuel Carrión Ulloa was an army officer before studying voice in Madrid. After just one year of training, he made

his debut in concert in 1842, and in opera in 1844 (Rodrigo in Rossini's Otello at the Teatro Circo). The next

years, he sang regularly both at the Teatro Circo and the Teatro de la Cruz, and in 1847 outside Madrid for the first time:

in Valencia; soon also in Sevilla and Cádiz. He specialized in Verdi, but sang also a lot of belcanto: Barbiere, Maria di Rohan,

Sonnambula, Lucia di Lammermoor, Lucrezia Borgia.

When he returned to Madrid in 1850 (first to the Teatro Circo, then to the brandnew Teatro Real), he had definitely won the

status of a superstar. From 1852, he made a great career in Italy: La Scala and Teatro Carcano in Milano, Teatro San Carlo

in Naples, Rome, Genova, Udine... he scored triumphs as Manrico, as Duca, as Gualtiero (Il pirata) or as Jean de

Leyde.

In 1855, he went on to Vienna (Kärntnertortheater), where he appeared in Mosè in Egitto (another of his

big successes), Rigoletto (less successfully, in Vienna), Don Giovanni, Barbiere and Cenerentola.

Later the same year, Carrión was in Paris, at the Théâtre Italien. His debut, in Mosè

again, got a chilly reception, but in Cenerentola, in Fiorina by Pedrotti, and in Rossini's Otello

(this time in the title role), his success grew from one evening to the next. He stayed, and in 1856 sang in Matilde di

Shabran and Don Giovanni. Then he went to Budapest and once more to Vienna, and in October back to Paris, where

he was ill-disposed throughout the season.

In 1858, success was back: Mosè and Guillaume Tell in Torino, Così fan tutte and

L'italiana in Algeri in Vienna. Then he returned to Madrid, after a seven-year absence, first as Edgardo, then

(rousing particular enthusiasm) as Elvino.

The next years were spent between Torino, Vienna and Paris; he added Robert le diable to his repertory, and scored

new triumphs in Italiana and Cenerentola. Not so in Madrid in 1861/62: while one part of the audience still

hailed him, another part found him meanwhile conceited and overbearing; corresponding battles in the auditorium included.

Carrión eventually passed the trial and won unanimous consent in Puritani and in "his" Trovatore,

where in that season he invented the high C on "all'armi" (now customary, but of course not written by Verdi). However,

after that rather upsetting season, he never returned to Madrid.

Where he did return was Vienna, Genova, and multiple times La Scala. Carrión sang, less frequently, until 1875, then

he lived in Milano as a voice teacher. One of his students was his son José, who made a tenor career, too, albeit not

on his father's level of excellence.

Reference 1, reference 2

Manuel Carrión in Berlin and Hamburg

The success of the tenor Carrión in Berlin was extraordinary, incredible. Each opera was for him a triumph. From the first

to the last performance, he won applause, curtain calls, celebration and honors. (...) The cheers were no less in

Hamburg for this talented tenor. The choice of the first opera fell to a magical Barbiere. With words, we cannot describe

the bravos and applause that greeted Carrión, and also Artot, Delle Sedie and Frizzi. There was great enthusiasm for the

serenata; for the Figaro & Almaviva duet; for the finale; for the quintetto; for the terzetto; in short complete enthusiasm.

To unanimous demand the graceful Spanish duet, sung by Carrión and Artot at the cembalo, was repeated. The public showered

the singers with flowers at the end.

Il Pirata, 21 April 1860

|

Emanuele Carrión

The well known tenor, our good friend, is dead. A cruel disease that suddenly attacked him, led him in a short time to his

grave. The artistic career of Carrión was a continuous series of triumphs. I can say that he was an exceptional tenor.

Who sang like him: la Sonnambula, Guglielmo Tell, il Barbiere di Siviglia, il Trovatore, la Cenerentola, and l'Africana?

Carrión sang those diverse kinds of music with such confidence that came from his musical education in the real school of

Italian singing; from his possession of the soul and talent of a real artist. The public of the main cities of Italy, and

the capitals of Europe, acclaimed him with great enthusiasm; wherever he was, he received enviable decorations. The Spanish

government had given him the order of Carlo III many years ago. This artist was a model, and at the end a mentor for the

young students – among them his son Giuseppe, who could be his dignified successor. Emanuele Carrión's death is a

loss for art, and for his friends the loss of a mild, gentle and honest man.

Il Trovatore, 30 July 1876

|

I wish to thank Daniele Godor for the lithograph.

|