![]()

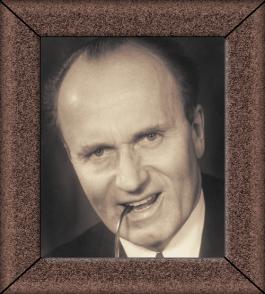

This issue of "Les Introuvables" is entirely dedicated to the Swedish heldentenor Set Svanholm (1904–1964). Svanholm was beyond doubt one of the greatest heldentenors of the 20th century but is unfortunately poorly represented on records. Many of his best roles like Siegfried and Tannhäuser were preserved on records – but under unfortunate circumstances. The Ring from La Scala under Furtwängler suffers from bad sound as well as another one from Buenos Aires under Fritz Busch. His only Tannhäuser – a 1953 Florence recording under Artur Rodzinsky – was made when Svanholm was badly indisposed. And Georg Solti, famous for his odd choices of singers, chose Wolfgang Windgassen for the role of Siegfried instead of Svanholm who only got to sing the smaller part of Loge in Das Rheingold. However, the Swedish record label Bluebell put some effort into keeping the memory of Svanholm alive, when they dedicated a number of their series "Great Swedish Singers" to Set Svanholm, including interesting clips from radio and private recordings of Otello and Freischütz as well as Strauss and Wagner operas. Unfortunately, some of the most interesting selections were presented in wrong speed. They don't do Svanholm's art any justice. Radio Hamburg made a recording of act 1 of Die Walküre with Birgit Nilsson in 1954, an interesting but dry and sterile sounding document. The Norwegian radio recorded a complete Götterdämmerung in 1956 with Kirsten Flagstad when both Flagstad and Svanholm were not anymore on the peak of their vocal powers. So as to hear Svanholm at his best, one should get the famous recording of Mahler's Lied von der Erde with Bruno Walter (New York 1948) or the Wagner pieces Svanholm recorded in 1947 with Eileen Farrell for RCA Victor. Many of his best recordings were not published and remained in the hand of collectors. This issue of Les Introuvables wishes to give access to some of the best recordings of Set Svanholm.

Set Svanholm studied together with Jussi Björling, Joël Berglund and Einar Beyron with the great Swedish baritone John Forsell in Stockholm. Forsell taught Svanholm a technique that is now seen as the classic Swedish school of singing, and not only Svanholm, but also other Swedish singers like Carl Martin Öhman and Torsten Ralf soon made the Swedish method world-famous. Typical for the Forsell school was the direct attack of higher notes, covered and in the mask – followed, if possible, by a gradual opening after the attack. All the great Swedish singers of that school had command of this technique; especially the heavier tenors like Öhman, Ralf and of course Svanholm.

Svanholm did not originally aim

at becoming an opera singer. His

biographer Erik Eriksson:

"Following organ lessons from his father, a Lutheran minister, Svanholm prepared for a teaching position and actually served a school near his home for a two-year period. Wishing to deepen his musical knowledge, he performed a series of organ recitals to amass the financial means to do so."

Being only 17 years old, Svanholm was the youngest organist in Sweden at that time. Later, Svanholm also sang as a cantor at St. Jacob's Church in Stockholm. At the conservatory, he first trained to be a baritone, graduated in 1925 and debuted at the Stockholm Opera as Silvio in Leoncavallo's Pagliacci in 1930, followed by appearances as Figaro in Rossini's Barbiere and King Olav in Petersson-Berger's Arnljot. In the follwing six years, however, he prepared for his debut as a tenor – according to Eriksson, following his wife's advice:

"Singing as a baritone for several years, he finally yielded to his wife's insistence that he was really a tenor and retired for re-training."

Björling's wife Anna-Lisa reports in her book that Björling and Svanholm used to compete during their years of study who could sing most high Cs in one afternoon. Svanholm's debut as tenor came in 1936, again in Stockholm, but this time as Radamès in Verdi's Aida. Roles like José (Carmen), Max (Freischütz), Vasco da Gama (L'Africaine) and Martin Sharp (Fanal) followed, as well as Manrico (Trovatore), Otello, Bacchus (Ariadne), Erland (Singoalla), Canio (Pagliacci), Laca (Její pastorkyňa), Andrej (Khovanshchina), Peter Grimes, Énée (Les Troyens), Samson, Herodes (Salome), the baritone part of Eisenstein (Fledermaus in English at the Met 1951) and the Wagner roles Erik, Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, Tristan, Walther, Parsifal, Loge, Rienzi, Siegmund and both Siegfrieds. In 1938, Svanholm sang at many major European opera houses like Budapest, Vienna (by invitation of Bruno Walter), Munich and the Salzburg Festival (Tannhäuser and Stolzing in 1938 under Furtwängler). In 1942, he debuted at La Scala and Bayreuth, singing the roles of Erik and both Siegfrieds. In 1946, he went to Buenos Aires to sing Tristan and again both Siegfrieds. The same year, Svanholm was appointed Royal Swedish Court Singer (Kungl. Svensk Hovsångare). Svanholm debuted at the Met in November 1946 (Young Siegfried) and regularly came back to New York for over ten years, often in Italian, Strauss and Wagner repertoire. His debut in London came during the season 1948/49 (again Young Siegfried). In 1951, he was Tristan in Kisten Flagstad's farewell performance at the ROH. During his many visits to the US, he also sang in Chicago, Washington, San Francisco and Los Angeles. In 1953, he appeared at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino as Tannhäuser. The same year, he became a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music where he remained active as a teacher until his death.

In 1956, he became the director of the Stockholm Royal Opera House. Bertil Hagman about Svanholm's fruitful work there:

"He established the collaboration with the Drottningholm Theatre, supported the writing of chamber operas, reorganized the Wagner repertoire and supervised many important productions by directors such as Ingmar Bergman and Göran Gentele, who was to succeed him as opera director. All in all, the period 1953–1963 were the golden years for the Stockholm Opera."

Svanholm's farewell from stage came in 1963, singing Tristan in Düsseldorf under the artistic direction of Wieland Wagner and a performance of Mahler's Lied von der Erde in Vienna. Shortly after, a brain tumor was diagnostizised. Bertil Hagman, who visited Svanholm in the hospital, recollects:

"I visited him afterwards, he said with some difficulty: I don't know yet whether it is a dangerous tumor. But if I am to die soon I cannot think of a more wonderful end to my career than to have sung Mahler in Vienna and Tristan on a German stage. I thank God for that."

Set Svanholm died on October 2, 1964.

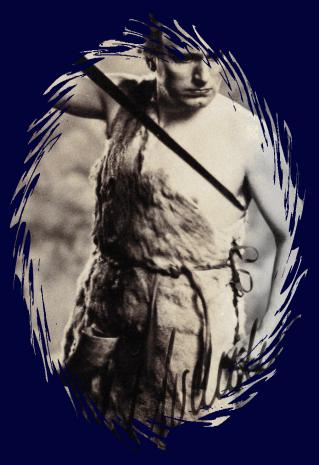

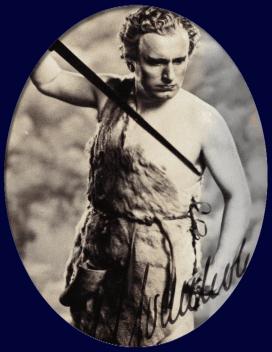

Set Svanholm was in many ways a perfect singer. He was intelligent, had an attractive physical appearance (one of the few singers who looked the part when singing Siegfried!), a slim, strong and indefatigable voice of true Nordic, light blue color with a solid technique. Svanholm's voice was able to cut even through the heaviest Wagnerian orchestration, and the intelligence of his interpretations made him – at least to my taste – a singer superior to many of his colleagues, including Lauritz Melchior.

![]()

Siegmund Set Svanholm

Sieglinde Hilde Konetzni

Orchester der

Wiener Staatsoper

Hans

Knappertsbusch

Excerpts:

1.

Winterstürme

wichen dem Wonnemond

About this recording:

This is one of the earliest live recordings of Set Svanholm. It was once published in the series "Edition Wiener Staatsoper live" which contained interesting live recordings made on wax matrix. The series is now out of print, and the recording was published – like some of the Bluebell issues – in slightly wrong speed. This defect has been corrected in the clips presented here. What can be heard is a manly, dark, but tenoral and powerful Siegmund who vocally sounded the part more than anybody else. Most tenors show fatigue at the end of "Siegmund heiß' ich", but Svanholm pulls off a high A that must have inspired the audience with awe. He also masters Knappertsbusch's extremely slow tempi in "Winterstürme" with admirable ease.

Source:

These excerpts have been published by Koch Schwann, "Edition Wiener Staatsoper Vol.19", Koch 3-1469-2A

NYPO

Bruno

Walter

Excerpt:

About this recording:

This recording is not at all hard to find, so here we have an exception from my "rare recondings only" rule. But I felt that no portrait of Set Svanholm would be complete without an excerpt from this wonderful performance from Carnegie Hall. I have never heard Mahler sung in such perfection by any tenor. Mahler's songs belong to the most difficult tenor literature. The way that Svanholm masters them at full voice (as opposed to Wunderlich for example, who never achieved that) without losing his clear and flawless diction is simply breathtaking.

Source:

Naxos Historical "Immortal Performances" series

Radamès Set

Svanholm

Aida Stella

Roman

Amonasro Leonard

Warren

Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera House

Cesare Sodero

Excerpts:

About this recording:

Radamès was one of Svanholm's best roles. When Bruno Walter heard him as Radamès in Stockholm, he invited him for his debut at the Vienna State Opera right away. At the Met, however, Svanholm was not the first choice for Radamès, a role that had been sung by Gigli and Martinelli – and the critics usually blamed him for his lack of italianità. Sure enough, Svanholm was a Radamds who sounded like Siegfried in the wrong play, due to the very Swedish way of singing and of course the color of his voice – but he was a Radamès who got just as passionate as his Italian colleagues. The clips presented here show a ravishing and fierce singer who handles the delicate role without any sign of difficulty. The demanding attacks on "Pur ti riveggo" and later in "Io son disonorato" are hammering through the orchestra and the rest of the ensemble – in the same style that Siegfried does his "Heia ho ho ho" in the forging song.

Source:

Private recording

![]()

Otello Set

Svanholm

Jago Sigurd

Björling

Swedish Radio Chorus and Orchestra

Sixten Ehrling

Excerpts:

(both selections are sung in Swedish)

About this recording:

Svanholm was a popular Otello both in Sweden and in the US – and he was the best proof for the fact that neither Otello nor Tristan are voice-killers when sung with a good technique and intelligence. Svanholm's sound in Otello is similar to that in Aida: fierce and vehement, but not bereft of subtle moments that baritenors like Del Monaco and Vinay often had their problems with. Again, some will have the feeling of "Siegfried in the wrong play", but then again, Svanholm's Otello is particularly impressive because he sang with style and did not save his voice in order to be able to get through the part. Svanholm gave everything from "Esultate" to "Un altro bacio" and demonstrated at the same time how one could get through the part without fatigue. Sigurd Björling's velvety baritone made a nice contrast to Svanholm's steely Otello. And the Swedish language added some funny effects too... ("fazzoletto" becomes "näsduk")! And one should not forget that Swedish is a very uncomfortable language for singing, full of narrow vowels like /u/, /y/ and /i/. Until now we have heard Svanholm in German, Italian and Swedish. The following selection will be in Latin.

Source:

Private recording

Stockholm PO

Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt

Excerpt:

About this recording:

No, Svanholm was not the roasted swan! He did the baritone part instead, showing that he was perfectly able to sing baritone while still being an excellent tenor – as opposed to Ramon Vinay who sang baritone parts when he had no voice left...

Source:

Private recording

Arne Sunegård at the piano

About this recording:

Svanholm in recital is an absolute rarity, as he never recorded lieder commercially. This is a private off-the-air recording of a recital Svanholm gave in Washington, singing songs by Schubert and Brahms. Svanholm is, as can be heard here, an old-style lied interpreter, singing at full voice in true heldentenor tone. The song demonstrates what a skilled "vocal actor" Svanholm was. Listen how his voice changes from the sinister whispering of the erl-king ("Ich liebe dich, mich reizt deine schöne Gestalt") to the desperate "yelling" of the distressed son and to the final line ("das Kind war tot"), which is sung in an ice-cold, horrified tone. This is definitely the most exciting rendition of the Schubert song that I have heard. I remember a lieder recital by James King where he sang Schubert and Strauss songs at full voice. Some were complaining about his operatic style when singing songs, creating a new, funny word in German: "Er opert schon wieder" ("He is opera-ing again!"). Well, I like it if singers are "operaing" when singing songs, I like to hear full voiced singing – that's one of the reasons for why I love this particular version of the Erlking. Fans of Fischer-Dieskau or Wunderlich will not be pleased.

Source:

Private recording