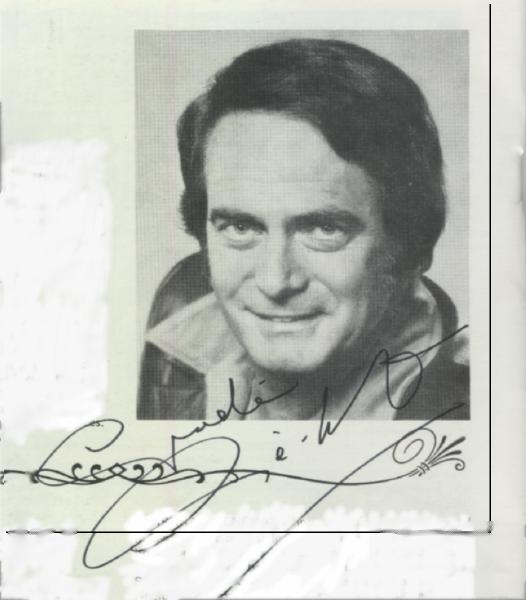

For the best part of three decades, no male opera singer in South Africa could hold a candle to Gé Korsten. It was

more than the undoubted quality of his voice, however, that made him a household name for whites in South Africa – he

also had shockingly good looks and buckets of charisma. He was also prepared to do what few, if any, serious opera singers

dared do in those days of artistic elitism – mix weighty, traditional opera with light, popular folk music. He became

the ultimate heart-throb for hundreds of thousands of mainly Afrikaans women, who travelled vast distances to hear and, more

importantly, look at him.

To others, though, there was something vaguely ridiculous about the way he brought his considerable operatic skills to bear

on the mawkish lyrics his fans lapped up. But, being the consummate professional that he was, there were never any half

measures. No one performance was any less important to him than another.

As much as he sang light music because he genuinely enjoyed it, Korsten clearly made a lot of money out of it. For all the

disparaging remarks he endured, his willingness to descend to the level of the masses did more for the cause of opera in

South Africa than anything else. People who would normally have run a mile at the mere mention of the word began flocking to

opera houses to hear their idol. They liked what they heard, and returned to hear more. In the 1970s, performances would

draw full houses, and for a chance to hear the likes of Korsten and Mimi Coertse, people would queue all night outside the

State Theatre in Pretoria.

Why he did not work overseas – as, for instance, Coertse did in the 1960s and early 1970s and Deon van der Walt and

Johan Botha later on – is a question often asked about Korsten. What few know is that Korsten, who arrived in South

Africa from Holland at the age of seven, began his working life as an electrical artisan. He began to develop his singing

talent (initially as a baritone before becoming a tenor) relatively late in life, receiving no formal voice training until he

was well into his 20s. The chance to work overseas presented itself in 1962, when he was awarded a bursary to study in

Vienna for a year – but by this time he was already 35 and had a business to run and a family to support. There is

little doubt that he could have built a career for himself in opera overseas if he had wanted to. After an audition at the

State Opera in Vienna while studying there, he was asked to take the place of a late withdrawal in Madama Butterfly.

Instead, he returned to South Africa and spent another ten years singing and running his business, which he sold in 1970 to

devote himself to singing professionally.

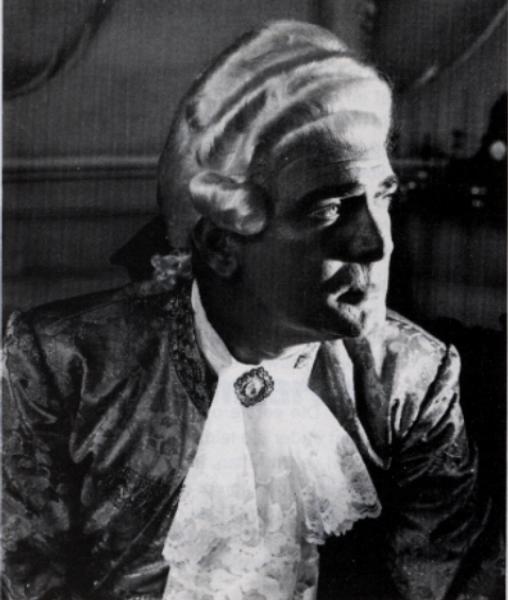

He appeared on stage more than 3,000 times, taking 23 roles in most of the major operas, but his finest hour was probably

his performance in Její pastorkyňa (Jenůfa), the 20th-century opera by the Czech composer

Janáček. For once he did not take the part of the glamorous hero. His character (Laca) was decidedly

unromantic and nasty, and for this alone his decision to take the role was courageous.