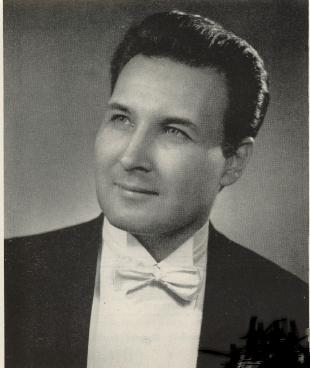

Eddy Ruhl, opera's most beautiful male singer besides Franco Corelli, is primarily remembered for

two episodes that shed a dark light on his brightness. One, he was offered to become the new Tarzan in the movie

series (I suppose after Johnny Weissmuller had to retire from the role) – and declined, going on with his mediocre tenor

career instead of becoming a celebrity like Weissmuller or Lex Barker. Two, at the Oslo opera in 1961, he refused to share a

dressing room with Charles Holland, which not only got him fired instantly, but also

got him memorized as the operatic world's most blatant racist (Holland was black, for those who don't know).

You'll regularly find Eddy Ruhl de-nicknamed as Edward, but in fact, he was born Edbert Kershaw Ruhl to a naval officer and an

opera singer. As he showed interest in singing early on, he got voice lessons by teachers that his mother handpicked for him. He

grew up in the upper class of Washington D. C., in a lavish 22-room residence, complete with servants. The Ruhls' neighbor was Evalyn

Walsh McLean, a mining heir who had in her collection two of the world's most famous diamonds, the Hope Diamond or Bleu de France

(now at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington), and the Star of the East. Her husband owned the Washington Post.

Eddy Ruhl married Evalyn Walsh McLean's personal nurse. Enlisted in 1944, he made use of his deployment to Italy for taking lessons with Aureliano Pertile.

Ruhl's career started with his close association with two divas, one actual and one... legendary, in every sense of the word.

Many of his early appearances took place in Baltimore, where Rosa Ponselle was involved in promoting opera, and eventually in

founding the Baltimore Civic Opera Company. Ruhl was one of Ponselle's young protégés, and he sang there regularly,

both before and after the foundation of the new company, in whose inaugural performance (28 April 1950) he was Radamès. And he

was also affiliated (both musically and privately) with Vassilka Petrova, the post-war Florence Foster-Jenkins; he figured as the

lead tenor in two of the wealthy lady's self-paid complete opera recordings (on the Remington label), Tosca and Cavalleria.

That set the tone for the rest of his career. He mostly sang in venues of secondary or minor importance, to mixed or

bad response nonetheless: for instance as Duca with the Suburban Opera Company in Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1965 (Ruhl sang also

Turiddu and Canio the same year with that company); as Grigorij in Fort Worth (with Jerome Hines, about 1960); as Pollione at the

Brooklyn Academy of Music with Herva Nelli in 1962 or 1963 (a spectator still cringed at the memory of that "truly awful

performance" some 36 years later on the web); Regina Resnik, who sang her very first Carmen in Cincinnati to Eddy Ruhl's Don

José, still shuddered at his singing decades later, as an old lady; and his records, not just those with Vassilka Petrova,

were always badly reviewed. Nonetheless, he regularly got some prestigious engagements; already in 1947, he sang for the pope at

the Vatican. He was Rodrigo in La donna del lago

at the Maggio musicale in Florence in 1958, under Tullio Serafin and with Cesare Valletti and Rosanna Carteri (a performance that

was recorded, and issued on LP). He appeared in Semiramide with Joan Sutherland in Los Angeles in 1967. And he sang regularly on

radio and TV, including a very early full-color TV production of Madama Butterfly on NBC.

In his later years, he lived in Hollywood, Florida, and taught voice.

Reference 1: Baltimore Sun, 15 October 2000; reference 2: Frank Hamilton, Opera in Philadelphia. Performance

chronology 1950–1974, online publication 2011; reference 3: The Dome, 16 December 1965; reference 4; reference 5; reference 6; reference 7 and picture source (top): www.eddyruhl.com (defunct); reference 8: New

York Times, 10 November 1987; reference 8