MAX LORENZ

INTRODUCTION

Max Lorenz

is a singer who polarizes both audiences and critics. In Germany, Lorenz is

considered to be one of the great dramatic tenors of the 20th

century, while his voice and musical skills, style and expression have a doubtful

reputation abroad. John Steane, author of The

Grand Tradition – Seventy Years of Singing, described Lorenz' voice as

unattractive and ugly. Irving Kolodin (The

Story of the Metropolitan Opera) meant that Lorenz' voice had a hard and

unpleasant quality, even though he appreciated Lorenz as a serious artist. More or

less famous German critics attested Lorenz a "voice of powerful

brilliance, capable of clear phrasing, a voice which, even in dramatic moments

never offended against the laws of bel-canto" (Helmuth Castagne in the booklet of the LP

edition Bayreuth 1936).

Friedrich Herzfeld (Magie der Stimme)

enthused: "Everything in him was radiant with power – his appearance and

his brilliant voice which even mastered Walter Stolzing's dangerous top notes

with charming nobility". And Jens Malte Fischer (Große Stimmen) praised his "razor-sharp diction" and

compared the power of his voice to a blade that was "victoriously"

able to cut even through the thickest orchestration. Fischer considered Lorenz'

recordings of Wagner's Tristan and Tannhäuser to be the greatest recordings of

these operas that were ever made.

The

judgements about Lorenz are inconsistent. This reminds of the case of Aureliano

Pertile. The Italian expert Giorgio Gualerzi called Pertile's voice

"probably the ugliest voice, seen from an objective point of view"

(magazine Opera, 1985), while Arturo

Toscanini called him his favorite tenor. Lorenz was, in spite of all the

critics, the leading tenor for the heavy Wagner repertoire in Bayreuth between

1933 and 1945, he sang at the coronation ceremonies in London in 1937 and was

Furtwängler's choice for the role of Siegfried in Götterdämmerung at La Scala in 1950. The truth lies therefore – as in Pertile's case – most

probably somewhere in between (if truth is the right word for something as subject to personal taste as music).

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

EDUCATION

In his

humorous autobiography from 1963, Lorenz frankly admitted: I am not called Max Lorenz. It is a pseudonym.[1] His real name was Max Sülzenfuß, and

he was born in Düsseldorf on May 10th, 1901. His father was a butcher with

his own shop, but without any comprehension of music: He wanted me to become his successor. But that did not interest me. I

wanted to become a singer. At any price. The fact that Lorenz actually gave

up his surname was a symbolic act of rebellion: in German, Sülzenfuß means

jellied pig's trotter.

But the beginning was not easy. It is told that Lorenz' voice was so ugly that his music teacher dismissed him from music lessons in school. Everybody who heard about my intentions said: you want to become a singer? That's ridiculous, you are hoarse! That's strange: My speaking voice is always hoarse. But the more huskily I speak, the better I sing! The education had to be done on the sly and against the father's will. He wanted the boy to learn a "decent" profession. A musical education was in his opinion nothing more than a waste of money. The boy was not even allowed to go to the opera. But Max went secretly, and during the years of dearth in the First World War, he organized the tickets by swapping them for sausages and gammons he had stolen from the father's shop. The black suit had to be hidden in the cellar. When his father caught him on his return from the theater he used, as Lorenz wrote, to give him a good thrashing. Only the mother was supportive and financed the boy's education. Lorenz studied with Pauli in Cologne – a city about 40 kilometers away from Düsseldorf: For over five years I secretly went to Cologne three times a week. When I came home in the evening I was not allowed to say a word about how it went. My mother just gave me a glance, which meant: "Was it good?" And I returned the look: "Very good".

After five years of studies, Pauli advised Lorenz to continue his education with Ernst Grenzebach in Berlin. Grenzebach had already worked with Melchior and Kipnis. But Berlin was 400 kilometers away, and trips over such a distance could certainly not be done secretly anymore. The father was furious, but it was the mother who got her way: I went to Berlin to see Grenzebach. While I was waiting for my turn I listened to Lauritz Melchior, the famous heldentenor. He was taking lessons with Grenzebach and I heard how he got dressed to size by the professor. That was enormously impressive. To me, the professor said: "Well, nice voice, but we would need to take away the rust first. You have to start over again."

And Grenzebach

was a very rigorous taskmaster. Lorenz, gifted with a strong body of impressive

size and athletic appearance, used to sing with full power. But Grenzebach

said: "When you practice, sing

piano! Always piano piano! I know that you are able to sing forte. But the

voice grows from the piano. You must be able to sing so low that nobody can

hear you even when you have the window open! The little will become a lot. Your

voice must be like a rubber band. When you pull, it becomes longer and

longer!" The consequent use of Grenzebach's method turned, as Lorenz

told in a radiobroadcast, the originally

lyrical voice into a heldentenor.

Lorenz had to meet Grenzebach every day, he was the first student to show up and the last to go home. When it was not his turn, he had to listen to the other students and learn from what he heard. He was not allowed to sing arias. Grenzebach told him just to sing single notes for a whole year. Grenzebach soon had full control over his promising pupil. For example, he held the view that it was absolutely necessary to go to bed early, and from time to time he checked whether Lorenz was at home at ten o'clock in the evening. If he did not meet him at home, he used to be in a very bad mood. If I showed up the next morning and had the slightest sign of indisposition, he used to say placidly: "Go home, this does not make sense! If you go out and are indisposed the next morning, the education is completely useless. If you want to become a singer, you have to make sacrifices. That is a fundamental condition!"

BREAKTHROUGH

After two

years of studies, Grenzebach allowed Lorenz to participate in a big contest for

amateur singers organized by a popular magazine (Hackebeils Illustrierte Zeitung). The event took place at the Berlin

Philharmonic Hall in 1926. I still remember

that the répétiteur said to me: "Stop laughing all the time!" I

laughed due to nervousness – I did not even notice it. But when it was my turn,

I sang. Next morning I received a telegram: I was the one out of 70 participants

who had won the first price. The same day, the Dresden State Opera [at that

time under the direction of Fritz Busch]

offered me a contract.

A couple of days later, I found my picture in an

illustrated magazine; I sent it home. And what did my good old father do, who

had always been an encumbrance to my career as a singer? He sent it to the

Illustrierte Fleischerzeitung's editorial office ("The Butcher's Illustrated

Newspaper"), announcing that his son was appointed to be the new heldentenor of

the Dresden State Opera!

It was of course not completely true that Lorenz' career in Dresden started in the heldentenor repertoire. His first role was Walther von der Vogelweide in Wagner's Tannhäuser, followed by the minor tenor part in Lortzing's Undine. It would not be true either to say that Lorenz had a walkover in those minor parts. I remember that the director, who sat somewhere in the back of the auditorium rose during the rehearsals for Tannhäuser and yelled: If you are that untalented you should sing in Meißen and not in Dresden! (Meißen was a small town with only a couple of thousands of inhabitants in the immediate vicinity of Dresden.) And in Dresden, there were Curt Taucher, kind of an idol to me, Paul Schöffler, Meta Seinemeyer, Elisabeth Rethberg, with whom I was going to sing later... all wonderful singers. Tino Pattiera [a Croatian tenore robusto for the Italian repertoire with an exiting but short career] was there too, and I had to learn all of his roles... La forza del destino, Turandot... Manon Lescaut.

In 1928, Lorenz sang his first main role: it was the part of Menelas in Richard Strauss' Die ägyptische Helena. A very difficult part, which is, like in so many other operas by Strauss, ungrateful since the technical difficulties and the achieved effect are blatantly disproportionate. Quite contrary to des Grieux in Puccini's Manon Lescaut, a role that Lorenz had to take over on short notice from the indisposed Pattiera during the season 1928/29. Des Grieux was followed by Radames in Verdi's Aida, Lorenz' second difficult main role, which he sang at the age of only 28 years. During the same season, Lorenz had to take on Alvaro in Verdi's La forza del destino (with Paul Schöffler as Don Carlo), Riccardo in Verdi's Un ballo in maschera, Manrico in Verdi's Trovatore, Max in Weber's Freischütz and Siegmund in Wagner's Walküre. The fact that Lorenz was able to take on the dramatic repertoire already at the very beginning of his career, without ruining the voice, proves that he must have possessed a good, solid and robust technique.

Besides his

activity as a dramatic tenor in Dresden, Lorenz gave recitals, singing classical

songs by Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. Excellent

for controlling the voice, as Lorenz said. His busy schedule of the years

that followed got in the way of a further commitment to lieder recitals –

something that Lorenz regretted very much.

DEBUT IN THE US

The role of

Radames was a milestone in Lorenz'

career. Lorenz told about a wondrous incident that occurred during his first

appearance as Radames: After the first act, a gentleman entered the

locker room; he was called Arthur Bodanzky, introduced himself as the artistic

director of the Metropolitan Opera and seemed determined to invite me to the US.

"What have you sung?" "Nothing that would be worth mentioning

besides Radames." "Come and visit me next summer in the Black Forest.

There we can rehearse everything we need."

Bodanzky

walked the talk and scheduled Lorenz' debut at the Met for the 1931/32 season.

The crossing from Bremerhaven to New York is legendary, since Lorenz was not

the only tenor on board. The great heldentenor

Rudolf Laubenthal, Armand Tokatyan, Richard Tauber and Jan Kiepura incidentally

had booked cabins on the same ship. What could better indicate the abundance of

good singers in those times than the fact that those five top-notch

tenors incidentally could meet on one boat? But for Lorenz, the crossing soon

became quite uncomfortable. He received a telegram from Bodanzky, in which the

conductor called Lorenz to prepare the role of

Tannhäuser, as well. A role I

did not know whatsoever. But Richard Tauber did me a great favor: during

the five days that the crossing took, Tauber rehearsed the role with me. Tauber

was definitely the right aide: In July 1926, he had to create the first German

performance of Puccini's Turandot

instead of the indisposed Pattiera. He worked wonders, and studied the role of

Calaf within three days!

During the rehearsals at the Met I failed many times,

since the part was completely new to me. But Bodanzky and all the other stars [Maria

Jeritza was Elisabeth] helped me, they wanted my debut to be a

success. The greatest, most famous colleagues always were also the kindest and most

modest ones. Everybody helped where they could. And there I have heard the

greatest singers in the world: Titta Ruffo, Claudia Muzio – Pinza. I actually

loved America very much. I sang Tannhäuser four or five times, and soon my

time in the US was over.

There are rumors that the story about the US debut as told by Lorenz is not entirely correct, or even fictitious. Jürgen Kesting referred to Kolodin's Met chronicle, which claims that Lorenz gave his debut in the role of Walther von Stolzing in Wagner's Meistersinger, and not in Tannhäuser. In his short biography, Erik Erikson pointed out that there exists a review of Lorenz' debut as Stolzing, which was, according to the review, received as the work of a "serious artist and an intelligent musician," though one afflicted with a "hard and unyielding tone quality". He was found a "credible" Siegmund and a positive Siegfried, albeit with the tonal shortcomings cited at his debut. A Lohengrin opposite Maria Jeritza was, as Erikson reports, described as "disagreeable in sound and unimpressive in appearance, the judgement on Lorenz's physical presence being at odds with contemporary accounts elsewhere". Jens Malte Fischer thought that Lorenz just misdated the whole story. Fischer believes that it took place in 1933, when Lorenz crossed the ocean for a second time. But the joint travel of the five tenors can be dated back to 1931. Walter Herrmann, author of one of the few Lorenz-biographies, held Lorenz' view. It's a fact that Lorenz made his Met debut as Stolzing, and that he sang Tannhäuser there only two years later, in December 1933, having crossed the ocean without Richard Tauber, this time. I suppose the Met asked him to prepare Tannhäuser already in 1931, but did not employ him in the role that year; because they actually performed Tannhäuser twice in November and December 1931, when Lorenz was in New York – but Tannhäuser was sung by Rudolf Laubenthal, who had been on board the ship too, after all.

Crossing the ocean: Lorenz, Laubenthal, Tokatyan, Kiepura, Tauber

STATIONS OF A CAREER

The year

1933 marked Lorenz' definite farewell from Dresden. He became a member of the

State Opera in Berlin and received his first invitation to Bayreuth. In Berlin,

Lorenz had to sing Radames, and

although he had a certain routine in that role, his nerves were all on edge. At 5 in the afternoon I suddenly got a panic

attack, took the telephone and called Leo Blech [the conductor of the

evening] to ask him to do the performance

without me. He said: "Just come! I guarantee you: you'll be fine, you will

sing well. I'm going to help you."

The performance was a great success. When everything

was over I went back to my locker room where I found a photography of Leo

Blech, signed with the following words: "The old Verdi sends his best

regards!" I took the photography with me as lucky charm whenever I had to

sing Radames.

In Berlin, Lorenz made the acquaintance of Heinz Tietjen, stage director and musical director in Bayreuth, who always was on the lookout for young talents. Tietjen did not only invite Lorenz to Bayreuth – he also prepared the 32-year-old for his debut at the Festspielhaus with enormous personal commitment. His rehearsals with Lorenz were lasting for weeks, two, four hours a day. During the summer of 1933, Lorenz debuted in Bayreuth singing Parsifal, Stolzing and Siegfried (in both Siegfried and Götterdämmerung). A program that no tenor of today would accomplish. Lorenz stayed loyal to Bayreuth and Tietjen, who had become Lorenz' first mentor and good friend: between 1933 and 1944, he appeared each summer at the Festspielhaus, singing Parsifal (1933 and 1937), Lohengrin (1936), Siegmund (1937), both Siegfrieds (every year from 1933 to 1942), Stolzing (1933, 1934, 1943, 1944) and Tristan (1938 and 1939).

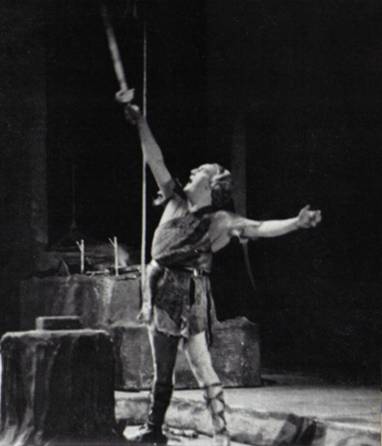

Siegfried (1930s)

Siegfried (Bayreuth 1936)

Lorenz soon became the leading heldentenor for the heavy Wagner repertoire in Germany and abroad. The fact that the peak of Lorenz' career coincided with the reign of the National Socialists had advantages and drawbacks. On one hand, one has to admit that Wagner's music has never been more promoted and subsidized than during the reign of Adolf Hitler. That was certainly conducive to Lorenz' career as a Wagner singer. The spirit of the time replaced the occidental religion with the concept of the Nordic ubermensch – and with Wagner. Performing Wagner's operas became an almost sacred affair itself.

In

Bayreuth, cherished as a Nazi temple of culture and provided with outstanding

artists, one could work without sorrow. Or, as Tietjen wrote: "Max Lorenz

on top of all, Prohaska, Maria Müller, Margarete Klose and the young

Greindl... only with those talented and quality-addicted artists I could, free from

anything earthly, invade the sanctum of art."

Germany

was, beyond doubt, home to some of the greatest Wagner performances ever.

And Lorenz was, as Tietjen pointed out, an important part of it. In 1936, the

Berlin State Opera presented Der

fliegende Holländer with Max Lorenz, Rudolf Bockelmann and Martha Fuchs,

Easter 1937 brought Parsifal with Max

Lorenz, Frida Leider, Ivar Andrésen and Erna Berger. In 1938, Lorenz sang Tristan in

Bayreuth with Germaine Lubin, and De Sabata conducting. Jens Malte Fischer

writes: "There are still many enthusiasts who hope for a tape of this

performance to appear. It promises unimagined delight, and those who actually

heard the performance live say that they've never heard anything better

in their whole life."

On the other hand, the political isolation of Nazi Germany had a disadvantageous effect on Lorenz' international career. Lorenz sang above all in Austria (which became part of Germany in 1938), Italy (part of the Axis), and countries that were relatively indifferent or even benevolent to Germany and its political system: Sweden, the Netherlands, Great Britain. In Vienna, Lorenz sang, from 1933 to 1945, Riccardo in Verdi's Ballo (1933 for the first time), Parsifal (1933), Tannhäuser (1936), Siegmund (1936), Siegfried (in Siegfried, 1937), Florestan in Beethoven's Fidelio (1937), Bacchus in Strauss' Ariadne (1937), Tristan (1940), Pedro in d'Albert's Tiefland (1940), Otello (1942) and Don José (1944).

Riccardo (Wien 1942)

Otello

(Wien 1942)

In 1937,

Lorenz sang Siegfried (Götterdämmerung) in Amsterdam with

Prohaska, von Manowarda, Fuchs, Heidersbach and Klose, under the direction of

Erich Kleiber. His debut at La Scala came in 1938, where he sang

Siegfried (both of them) and

Siegmund (replacing the indisposed Franz

Völker) under the direction of Victor De Sabata. His performances must have

been very impressive, because shortly after, Lorenz got invested as

Commendatore – a title which made him

very proud. I was about to leave Milan

when I had a talk with Mataloni, the artistic director of La Scala: "Mr.

Lorenz, I would like you to stay here at La Scala for the next couple of years.

But I want you for the Italian repertoire. I have observed you during today's

rehearsals. I would like you to sing Boito's Nerone here in our house!" In fact, I returned to Milan a couple of

weeks later and started rehearsing Nerone. But the atmosphere remained alien to me, and I returned to Berlin and

Bayreuth. Lorenz came back to La Scala in 1939 and 1942, both times singing

Tristan with De Sabata. The fact that Mataloni wanted Lorenz to sing

Nerone underlines the similarity of his voice

and Pertile's. It was Pertile who had created the role of

Nerone, and his recordings of scenes from that opera are often

deemed his best.

The Maggio

Musicale Fiorentino invited Lorenz in 1941.

London heard

Lorenz' Siegfried on the occasion of

the coronation ceremonies in 1937.

with Fuchs and Völker in

Bayreuth

with his wife and Rosvaenge

Some

historians absolutely insist that Lorenz was one of Hitler's personal protégés,

the "Third Reich's star-tenor, generally the leading tenor in the Third

Reich, Hitler's favorite" (Fischer). It is true that Lorenz was the

busiest tenor in the Third Reich and that his athletic physical appearance

served the propagandized image of the Nordic superhuman perfectly – in

contrast to Franz Völker, the leading lyrical heldentenor in Nazi Germany's

Bayreuth. Some even said that his musical style, a certain tendency to press

forward when the orchestra was conducted too slowly, reminded of the German

"blitzkrieg strategy, which of course suited the roles very well"

(Fischer). But Lorenz was, from a political point of view, not that easygoing.

Lorenz' wife, Lotte, was Jewish – a fact that brought Lorenz in conflict with the authorities after the passage of the Nuremberg racial laws in 1935. Legal proceedings against Lorenz and his wife were soon initiated since § 1.1 of the new law specifically prohibited the marriage of Jews and "citizens of German blood". The whole affair went to such lengths that Lotte Lorenz was not allowed anymore to visit performances in Bayreuth, and even got attacked by SS men in public. A court case because of the violation of § 1.1 was dangerous, and could make the accused end in prison or a concentration camp. And the cases of Tauber and Schmidt had proved that the National Socialists were ruthless even when it came to famous artists. But Lorenz had powerful friends – one of them was Winifred Wagner, Richard Wagner's daughter-in-law, a close friend of Hitler since 1923 and one of the few persons that were allowed to address Hitler informally (Du instead of Sie).

Lorenz

denied filing for divorce – successfully, probably thanks to the protection of

influential friends. He even coerced those SS men who had attacked his wife

into personally apologizing for what they had done: Lorenz had threatened never

to sing in Germany again unless the offenders apologized to her. The fact that

Lorenz was not part of the spectacular representation of Wagner's Meistersinger on the occasion of the huge

party congress Reichsparteitag

der Freiheit in Nuremberg was perhaps caused by the constant disgruntlement

between him and the authorities. The part of

Walther von Stolzing was then sung by B-tenor Fritz Wolff, who was

surrounded by an excellent cast that included Carl Kronenberg (Sachs), Josef von Manowarda

(Pogner), Herbert Janssen (Kothner), Maria Müller (Eva) and Wilhelm Furtwängler.

The court

case against Lorenz and his wife was not the only attempt to separate them.

Friedelind Wagner, Winifred's and Siegfried's daughter, tried to

convince Lorenz of filing a divorce and marry her instead.

But Lorenz stayed loyal to his wife. Friedelind, originally a fanatic Nazi,

suddenly changed her opinion about Hitler in 1940 and emigrated. When the war

was over and Lorenz was about to continue his career in the US, she tried to

frustrate it by spreading the rumor that Lorenz was a Nazi.

Friedelind with Hitler

Bayreuth 1938

Lorenz'

marriage was not the only cause for conflicts. According to Marcel Prawy (Jan

Kiepura's former chief secretary) Lorenz was "a prominent homosexual".

In 1936 the authorities tried to ban Lorenz from further appearances

in Bayreuth. Again, Winifred Wagner held her protective hand over Lorenz. In a

private talk with Hitler, Winifred achieved that Lorenz could

continue.

Lorenz was,

as his biographer Walter Herrmann points out, far from being a Nazi. From time

to time he was hiding fugitives in his house and organized their emigration

from Nazi Germany. Emigration was obviously out of question for him. He was

dependent on German language and art, and closely

connected to his home and his native country.

DAS SÜSSE LIED VERHALLT

Lorenz was not affected by any denazification provisions after the war; obviously, nobody

perceived him as a Nazi, neither in Germany nor abroad. In winter

1945/46, Lorenz returned to Vienna to sing Otello

with Hilde Konetzni as Desdemona and

Paul Schöffler as Iago, under the

direction of Karl Böhm. He added another extremely difficult part

to his repertoire: German in

Chajkovskij's Pikovaja dama, which he

sang for the first time in Vienna in 1946. The BBC invited Lorenz at

Christmas 1946 to sing Siegmund in

Wagner's Walküre – a special recognition,

also in political terms.

In 1947 Lorenz sang Tristan in Paris (together with Flagstad), his first post-war performance in a country which had been occupied by the Nazis. Everywhere in the opera house one could feel an icy front, especially the orchestra and the stagehands openly showed a hostile attitude. The performance went very well, but the moment after the final chord was awful. It is not exactly a very comfortable feeling to stand on stage without knowing how the audience is going to react. The whole house was deadly silent, but then everybody raised and applauded enthusiastically.

One year

later, Lorenz was heard as Tannhäuser at the Teatro

San Carlo di Napoli, together with Tebaldi as

Elisabeth and Rossi-Lemeni as Landgraf.

Between 1948 and 1952, Lorenz sang regularly at

La Scala: Tristan in 1948 (with Flagstad and Schöffler) and

1951/52 (with Grob-Prandl, Sigurd Björling and De Sabata conducting), in 1949 for

the first performance of Die Walküre

(with Flagstad, Reining, Höngen and Frantz) and 1950 for the performance of the

complete Ring under the direction of

Furtwängler.

But La

Scala was again also interested in Lorenz' Italian repertoire, especially in

his Otello, which they wanted him to

sing in Italian (all the performances in Vienna were sung in German). But

Lorenz refused again, because he thought that his Italian would not be good enough. Lorenz had

only sung the role of Otello twice

before in the original language, and that was in Paris. Later, the director of

the RAI, Fidia Schiavoni, told that he actually had seen one of the

performances of Otello in Paris and

remembered that Lorenz' Italian was excellent. He was convinced that Lorenz'

Otello in Italian would have been a

great success.

In 1947/48

and 1950 Lorenz returned to the US, performing

Tristan, Tannhäuser and Siegmund

(in Wagner's Walküre with the great

Swedish baritone Joel Berglund) and, in 1950, again

Tannhäuser and Lohengrin with

Astrid Varnay as Elisabeth and Ortrud.

A

performance of Tristan at the

Teatro Grattacielo in Genova in 1948 coupled him

with a young soprano, who would become one of the greatest stars in opera only

a couple of years later: Maria Callas. Lorenz as

Tristan, Callas as Isolde,

Nicolai as Brangäne and Rossi-Lemeni

as the King, Tullio Serafin

conducting. There are actually unconfirmed rumors that a recording of that

performance exists. Even Maria Callas was looking for it, as we can read in

a letter that she wrote to Lorenz in 1968:

"Dear

Max – I hope you remember me from the olden days when we sang together. I shall never

forget our joint performances. I hope you are well and content with your

life. (...)

I wonder if

it is true that you have a tape of our 'Tristan'. I was told that you

have one, and I would be so happy if I could have a copy for my personal

pleasure. Could you write to me if so – and anyway I would so like to hear from

you.

Much

affection and hoping to hear from you

I remain

yours –

Maria

Callas"

Lorenz

remembered Maria as an excellent

Wagner singer, just as Maria Callas remembered Lorenz as an amiable

colleague. In 1956, on the occasion of a performance of Lucia di Lammermoor in Vienna, Callas and Di Stefano invited Lorenz

for dinner to their hotel. It is a less than well-known fact that Lorenz was

one of the first mentors of young Di Stefano.

with Callas, Wien 1956

But

in spite of his international success, Lorenz' career began to draw to a close.

The overwhelming power of his voice started to run dry – surely due to

natural wear after more than 20 years in the dramatic repertoire. His

performances became less and less frequent, and a certain turn away from

the heldenfach in favor of the charakterfach was a logical

consequence of vocal decline in the mid-1950s. But Lorenz was, at

least as for the Vienna State Opera, still the first choice – a fact that

proves that the artist Lorenz was made of something more than "just"

a voice. In Vienna, Lorenz was now focused on the operas of Richard

Strauss, first of all, and on modern opera. In 1949, he added Herodes

(Salome) and

Äghist (Elektra) to his

repertoire. In 1953 he created, on personal request by the composer Gottfried

von Einem, the role of Josef K. in

the first performance of the opera Der

Prozess after Kafka. In 1954, he created the main role in another world premiere:

Podestà in Rolf Liebermann's Penelope. The following year, he appeared in

Alban Berg's Wozzeck in the small part

of the Tambourmajor.

Herbert

von Karajan's takeover as the director of the Vienna State Opera marked the

definitive end of Lorenz' career. Karajan was, in this respect comparable to

Solti, not only a musician but also a manager. And as the manager of the Vienna

State Opera, it was his ultimate ambition to make as much profit as possible.

This meant nothing else than the destruction of the old Vienna troupe in

favor of international jetset star casts or, as he called it, "a common

market for the arts". And Karajan unleashed a real

"star carousel", wearing out one singer after the other. In his

understanding of opera, in his conception of sound, the orchestra played a much

larger role than before, ceased to be mere accompaniment and became the dominant

element. The permanent rotation meant a constant source of stress, and the

excessive demand to sing over a symphony orchestra ruined many talented singers

and initiated the general decline of the art of singing. The "new

style" of performing and the international stars, which Karajan took along

to Vienna, soon made Lorenz dispensable. The break between him and Karajan can

maybe be compared to the irritation between Björling and Solti. Solti was, like

Karajan, a conductor-producer with new ideas of the orchestra's role within

opera, and without any sense for classic theater troupes, which (in his opinion)

were old-fashioned and not suitable for the actual market. The unscrupulous

sacking of Björling (1960) and Lorenz (1956) definitively meant the end of the

old tradition.

Lorenz quit

the State Opera and switched to the smaller Vienna Volksoper, singing parts like

Orphé in Offenbach's operetta and Buffalo Bill in Irving Berlin's musical Annie get your gun (1957). The parts I sing become smaller and smaller

the older I get. But it is great to observe the young generation. And from time

to time one of the young comes to me and asks: "Mr. Lorenz, how did you do

that then?" And I am glad to tell them about it.

Teaching James King

In

1962 Lorenz returned to the State Opera for one last performance:

Herodes in Salome, definitely his last

appearance on stage. It was not a happy farewell. Lorenz was, as legend has it,

afflicted by his displacement by Karajan, and unable to take

curtain calls so as to say goodbye to the beloved audience; he left the house

through the side exit.

After

his farewell Lorenz was appointed to a professorship at the Salzburg Mozarteum. Among his most famous pupils

were the tenors Jean Cox and James King. And for a third and last time, Lorenz

declined an offer from Italy: a professorship at Santa Cecilia in Rome.

He

died on January 11 1975.

Lorenz'

renditions are characterized by a strong declamatory and expressive style,

paired, as Jens Malte Fischer wrote, with a "razor-sharp diction". Lorenz

thought that expression and the beauty of sound (made possible by a solid

technique) were often conflicting: I do not care if some notes sound ugly. And he made perfectly clear

that the beauty of sound was not always the most important thing for him: It is the expression that counts. The

declamatory gesture demands expressions that conflict with the golden rules of

the art of belcanto. It's not only about emotional outbursts like shouting,

screaming and crying, but also about the color of vowels, which, in certain

moments, has to be more open or closed, brighter or darker. It happens, for

example, that a high G or even an A flat is taken completely open. The liquid

and nasal consonants (like r, n, m) are pronounced with extreme intensity.

It even occurs that the musical line and single notes are sacrificed to

expressive eruptions.

Opposed

to that, we have Lorenz' warm, beautiful and powerful voice. Listening to

his recordings, it seems improper to call his voice metallic. It surely has the brilliance of Björling's steel

and Lauri Volpi's squillo, but it did not

have that "two-fisted" presence and tension that Björling,

Svanholm and Melchior had in their voices. Lorenz' voice is not a bright, hard

element, its state of aggregation is fluent, not like water, rather viscous and

dark like crude oil.

The

fact that Lorenz is by far more popular in Germany than abroad is a consequence of the

language barrier. If you don't understand the words that Lorenz expresses in

music, you miss the half of the performance, and what remains is just

expressive impetus and rhetorical exaggerations.

Another

thing that is to listeners alike is Lorenz' presence on stage, which was an important part of his

performances and must have been very impressive, as many testimonies by

his former colleagues confirm. Belcanto

Society's videotape Legends of opera contains

a short clip of a rehearsal of Götterdämmerung

in Bayreuth from 1934, with Frida Leider, Heinz Tietjen and Karl Elmendorff

conducting, a clip that confirms those testimonies. It even seems that his

appearance compensated the language barrier: His successes abroad (in

Sweden, England, France and Italy) suggest that.

TESTIMONIES

"Why

was he unique? Max Lorenz was an exceptionally gifted artist – nature gave him

a glorious tenor-voice and a body, which was classically beautiful in every

movement, in every position. Furthermore he was warmhearted and had such a

powerful inner imagination, which made him become

the characters he portrayed on stage. His great art produced the impression of

being completely natural and unmannered." Winifred Wagner

"It

was an incredible situation to be on stage together with Max Lorenz. That

singer was in every sense the implementation of what I had been looking for for

years: A Meistersinger, who deserved the title well." Astrid Varnay

"In

spring 1954, I sang in Vienna for the first time (...). The great Max Lorenz was

my Siegmund, and I also experienced what many other colleagues had told me

about him: he encouraged me, he helped, and he cared. He taught me what it

means to have a really good colleague."

"He

was Lohengrin and Siegmund in my performances, an exceptional singer and actor,

and when we met for the first time, he greeted me with the following words:

'Kyss mig i arslet!' ('Kiss my ass'). I begged his pardon, but he repeated the

sentence in an even more sonorous Swedish. I understood that I did not mishear,

and there was an explanation, too. In 1936, Max Lorenz had given a couple of

guest performances in Wagner's Ring in Stockholm, and that's where they had

taught him this unpolished address of welcome. Max was obviously very proud of

having command of it, and I pretended to be flattered." Birgit Nilsson

"Dear

Max! Back to my 'Vikings' after a long journey through Europe, I would like to

thank you for all the great time we've had together. For me it was like

re-experiencing our youth and prime. I hope that the Lord is going to keep

you healthy and fresh for many more years and that we will meet again. Our

friendship will last until we will sing our songs with a harp in our hand

sitting on a cloud.

Keep

your throat moist!

Your

old comrade and friend Lauritz" Lauritz

Melchior

at home with Melchior

REPERTOIRE

| BEETHOVEN | Fidelio | Florestan |

| BERG | Wozzeck | Tambourmajor |

| BERLIN | Annie get your gun | Buffalo Bill |

| BIZET | Carmen | Don José |

| CHAJKOVSKIJ | Pikovaja dama | German |

| D'ALBERT | Tiefland | Pedro |

| EGK | Irische Legende | |

| VON EINEM | Der Prozess | Josef K. |

| GLUCK | Iphigénie en Aulide | Achille |

| GRAENER | Prinz von Homburg | Prinz Friedrich |

| HEGER | Bettler Namenlos | |

| VON KLENAU | Die Königin | Roberto Devereux |

| LIEBERMANN | Penelope | Podestà |

| LORTZING | Undine | Hugo von Ringstetten |

| MASCAGNI | Cavalleria rusticana | Turiddu |

| MOZART | Idomeneo | Idamante |

| MUSORGSKIJ | Boris Godunov | Dmitrij |

| PFITZNER | Palestrina | Palestrina |

| PUCCINI | Manon Lescaut | des Grieux |

| Turandot | Calaf | |

| STRAUSS, R. | Ariadne auf Naxos | Bacchus |

| Salome | Herodes, Narraboth | |

| Elektra | Ägisth | |

| Rosenkavalier | Italienischer Sänger | |

| Ägyptische Helena | Menelas | |

| Frau ohne Schatten | Kaiser | |

| VERDI | Aida | Radames |

| Ballo in maschera | Riccardo | |

| Forza del destino | Alvaro | |

| Otello | Otello | |

| Trovatore | Manrico | |

| WAGNER | Fliegender Holländer | Erik |

| Götterdämmerung | Siegfried | |

| Lohengrin | Lohengrin | |

| Meistersinger von Nürnberg | Walther von Stolzing | |

| Parsifal | Parsifal | |

| Rheingold | Loge | |

| Rienzi | Rienzi | |

| Siegfried | Siegfried | |

| Tannhäuser | Tannhäuser | |

| Tristan und Isolde | Tristan | |

| Walküre | Siegmund | |

| WEBER | Freischütz | Max |

COMMENTED SELECTIVE DISCOGRAPHY

Lorenz'

recorded legacy is very large. Most are

live recordings. Listed and commented below are a selection of

his best ones.

a) Complete operas and highlights

Wagner: Siegfried, excerpts w/ Tietjen, Bayreuth live 1936

One of Lorenz' best recordings. The sound quality of

the CD is unfortunately not good. Not only the noise but also the ring of

Lorenz' voice has been removed. The LP with the same title is the better

choice.

Wagner: Der fliegende Holländer, highlights w/ Flagstad, Janssen; Fritz

Reiner, London live 1937

A dream cast with Lorenz in very good form. As far as I know the only live

recording with Lorenz and Flagstad together besides the Ring from 1950. The

sound quality is OK.

Verdi: Un ballo in maschera, excerpts w/ H. Konetzni, Ahlersmeyer; Karl

Böhm, Wien live 1942

Interesting document. Lorenz sings the role of Riccardo (including the

high C at the end of the duet) without any effort.

Wagner: Rienzi, abridged w/ Klose, Scheppan; Johannes Schüler, Dresden

live 1942

This

is one of the first recordings that were made directly on tape. The singing is

good but sound is a bit obtrusive.

Wagner: Meistersinger w/ Prohaska, Müller, Greindl; Wilhelm Furtwängler,

Bayreuth live 1943

Very good sound. One of the best recordings of this opera.

Wagner: Tristan und Isolde w/ Buchner, Prohaska; Robert Heger, Berlin live

1943

Obtrusive sound. Lorenz sings the duet and the entire 3rd

act with nervous emphasis and febrile intensity.

Wagner: Die Walküre, act 1 w/ Teschemacher, Böhme; Karl Elmendorff,

Dresden 1944

In this recording Lorenz sounds a little overeager. A certain tendency

towards a "wobble" is evident. But Teschemacher is a wonderful

Sieglinde, maybe the best since Lotte Lehmann. Karl Elmendorff conducts in big

lines which suite the music very well.

R. Strauss: Ariadne w/ M. Reining, P. Schöffler; Karl Böhm, Wien live 1944

Good sound and singing. Authentic Strauss document made by Strauss' favorite

musicians.

Wagner: Die Walküre, excerpts w/ H. Konetzni, A. Böhm, I. Björck; Sir Thomas Beecham, London live 1947

One of Lorenz' best recordings, electrifying conducting by Beecham. The

sound is OK.

Wagner: Götterdämmerung w/ Flagstad; Wilhelm Furtwängler, Milan live 1950

Again Lorenz in very good form. The only possibility to hear his

complete Siegfried.

Wagner: Tristan und Isolde w/ Grob-Prandl, Björling; Victor De Sabata,

Milan live 1951

The cast of this recording is wonderful. Unfortunately very poor sound.

b) Recitals

"Max Lorenz – The complete Electrola recordings 1927–1942:

Meisersinger, Walküre Tannhäuser, Carmen, Aida, La Juive, Evangelimann,

L'Africaine, Forza, Pagliacci, Lohengrin, Rienzi, Siegfried, Lieder by von

Weingartner and Hildach (Preiser)

"Max Lorenz – Arias and duets": Tannhäuser

(1930), Lohengrin (1928/29), Meistersinger (1927/28), La forza del destino

(1929), Rienzi (1930), Holländer (1930), Ja Juive (1929), Carmen (1929),

L'Africaine (1930), Aida (1928/30), Pagliacci (1929) (Minerva)

These two recitals are a collection

of Lorenz' early studio recordings. The renditions of Lohengrin, Tannhäuser and

Forza are among his best recordings.

"Max Lorenz": excerpts from Die Walküre w/ Reining and Arthur

Rother (1941, from Ein Schwert verhieß

mir der Vater to the Finale of act 1),

Siegfried (1938), Holländer (1948), Parsifal (1933), Lohengrin (1948/53), Aida

(1952), Forza (1952), Otello (1952), Pagliacci (1952), Annie get your gun

(1957) (Myto)

Interesting

collection of rare live material. The recording of Celeste Aida is taken from

the complete recording issued by Myto. The excerpt from Otello (Niun mi tema)

is very impressive – it is a pity that a complete recording of Lorenz' Otello

does not exist.

The other clips from Forza and Pagliacci

demonstrate that Lorenz was still in very good form in the early 1950s.

"Max Lorenz singt Richard Wagner": excerpts from a 1950

broadcast of Siegfried and Götterdämmerung w/ Helena Braun and Arthur

Rother conducting, plus excerpts from Tristan w/ Christel Goltz and Ferdinand

Leitner conducting (1950) (Preiser)

Good, atmospheric "remake" of the

1943/44 performances. Good sound.

Also available:

Wozzeck (Vienna 1955), Der Prozess (Vienna 1953), Penelope (1954), Aida (Frankfurt 1952), Palestrina (excerpts, Vienna 1955), Elektra (Vienna 1957), Salome (Vienna 1951), Salome (Frankfurt 1952), Tristan und Isolde (Hamburg 1949), Tristan und Isolde (Buenos Aires 1938).