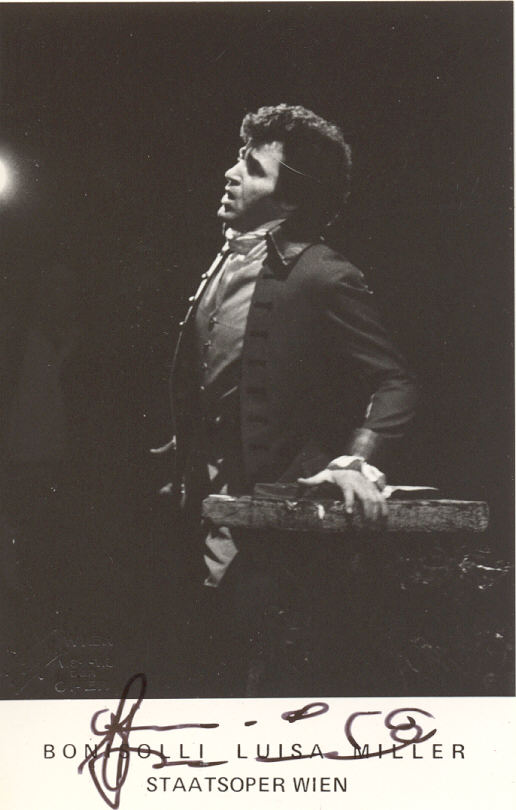

Franco Bonisolli

25 May 1937 Rovereto – 30 October 2003 Vienna

Originally a ski instructor, Bonisolli won the 1961 singing competition in Spoleto, where he

made his debut the following year at the local festival as Ruggero in La rondine, and where he also had his first major

success, again one year later, as the Prince in L'amour des trois oranges by Prokofyev.

His career soon gained steam. Already before the Prokofyev in Spoleto, in March 1963, he had made his debut at the Teatro

dell'Opera in Rome. In 1965, he was Puccini's des Grieux in Amsterdam, in 1969, he made his debuts at La Scala (in

L'assedio di Corinto, he was a Rossini specialist in his early years) and in San Francisco (as Alfredo), in 1971 at the Met

(as Almaviva), in 1972 at the Vienna Staatsoper (as Duca; by the way, forget what you read most everywhere that he started singing at the

Staatsoper in 1968). He sang in Toulouse, Bordeaux, Lyon, Brussels, Hamburg, Dallas, Philadelphia. In 1974, he was at the

Paris Opéra for the first time (Arrigo), in 1977 in Monte Carlo (Hoffmann), in 1981 at Covent Garden (Vasco da Gama),

in 1982 at the Deutsche Oper Berlin (Dick Johnson). At the Arena di Verona, he sang from 1985 to 1989 (Manrico, Radamès, Enzo,

Calaf).

Probably the most important theater for him was the Vienna Staatsoper, where he appeared 188 times from 1972 to 2000: as

Manrico (38 performances), Duca (20), Rodolfo in Luisa Miller (18), Alvaro (15), Cavaradossi (10), Riccardo (10), Rodolfo in

La bohème (9), Dick Johnson (9), Barinkay (9), Turiddu (9), Edgardo (7), Gounod's Faust (7), Chénier (6), Radamès

(5), Alfredo (4), Pinkerton (4), Calaf (3), Loris (2), Otello (2), plus one charity concert. At the Met, he was far less

successful, singing 25 performances without great approval by the press or the audience: Manrico (7), Gounod's Faust (5),

Alfredo (4), Cavaradossi (4), Duca (3), Nemorino (1), Almaviva (1).

He divided the public like nobody else, and he still does. Conceited, impulsive if not outright aggressive, radically uncooperative, and crazy

beyond imagination, he continuously damaged his career and reputation; the most blatant incident, also in that respect,

occurred at the Vienna Staatsoper, where in 1978, during the final rehearsal for the brush-up of an older Trovatore production

under Herbert von Karajan, he got so upset with the almighty conductor that he threw his sword down at Karajan's feet and left

the rehearsal, and the production (the opening night was "saved", or ruined, by Plácido Domingo): a really big scandal,

and a burden for the rest of

his career. He didn't care, or more probably he couldn't. Self-control was completely alien to him. But that was, at the same

time, what made him so exciting: he could heat up an audience like absolutely no other singer after WWII. Opera may have had a

shot of circus in Bonisolli's interpretation, but it (and he) never bored, on the contrary; he always gave everything, no

restraint, no caution, no safety net.

Bonisolli anecdotes abound. Just two examples: when he rehearsed Fanciulla del West in Berlin with Sinopoli, he noticed that

Domingo was in the audience. "Plácido, what are you doing here?" – "I'm here to learn something, Franco", was

Domingo's courteous reply. It earned him a far less courteous "But you're older than I am! It's too late for you – get

lost!"

One summer in Verona, Bonisolli rode his bicycle through the narrow lanes of the center. On a corner stood Carlo Bergonzi, and saluted Bonisolli: "Hello great maestro, how are you?" Bonisolli did

not feel flattered: "And so you hope that I'm going to say that the true great maestro is you??!! Fuck you!" He pedaled on,

and left a speechless Bergonzi.

His vocal technique was sublime, but he didn't always feel like using it. When he was in

too good voice, he often wouldn't care much for technical questions, or for nuances; and when his (inevitably short) temper

got the better of him, he was able to belt the whole evening like a German shepherd. Whenever, on the other hand, he was less

than well-disposed, he would sing his most memorable evenings since in those instances, he luckily remembered his technical

know-how, which definitely belonged into a different, much earlier age and had no equal after WWII. Although I've seen terrible

Bonisolli performances, I've also never seen, and will never see, another tenor half as good as he was.

One of my most striking Bonisolli experiences was one of his last

evenings: in autumn 1990, he had retired, immediately

after a really disastrous Otello performance at the Wiener Staatsoper;

furthermore, his wife fell seriously ill, in fact she was dying in a many

years long painful process – and Bonisolli tended her all that time. After she had died, he made a comeback in spring

2000, after a nine-and-a-half years long absence, and after a few concerts,

he returned to the Vienna Staatsoper for a total of five performances, the

best of which was one single Tosca where he sounded like 20 or 25 years

earlier. The young standing room habitués didn't know him anymore, and

didn't know anything about the former battles pro and con Bonisolli... and

the fascinating thing was how they, hearing him for the first (and probably

only) time, reacted to him – they were so enthusiastic, I suddenly realized

I hadn't heard such an applause for ten years. The Tosca was Eliane Coelho,

who sang the role often and with mixed results in Vienna, but on that

evening she was great, almost up to Bonisolli's standard; and she, too, was

totally stoned at the end of the performance because she obviously had never

before heard such a frenetic applause (from which she would of course

benefit, as well). When the iron curtain was already closed, the audience

was still shouting and applauding in ecstasy, and Bonisolli came out of the

front box on the right side of the stage, climbing over the balustrade and,

balancing over the ledge (just a few centimetres large) between the box and

the stage, above the orchestra pit, thus arriving in front of the iron

curtain and taking the applause once more; he wanted to make Coelho join

him, but she didn't dare to do the climbing and stayed in the box, and

was really swept off her feet about all this enthusiasm, I'm sure she

spoke of that evening for the rest of her life... Do I need to stress that nobody has been

able to rouse a similar enthusiasm in Vienna ever since? Nothing that came

only near it – just the aseptic excitement inevitably induced by the ticket

prices (if the tickets are expensive, I must think it's a great experience,

or I'd be annoyed at having spent so much for so little).

To sum it up, hating Bonisolli may be fine for people who listen to baroque opera only, or

to Schubert operas, or maybe for Wagnerians... for everybody else, it's pure

knownothingism. An interpretative approach like Bonisolli's is essential for

Italian opera; I don't say all singers must do Italian opera like he did (in

fact, I'd even be opposed to it), and of course I appreciate the Schipas and

Sabbatinis, too – but if nobody is supposed to sing Italian opera in the

Bonisolli manner, Italian opera will soon be sounding as if composed by

Schubert, or Rameau, or Wagner. (It already does, in fact.)

Reference 1, reference 2: archives of

the Vienna Staatsoper, reference 3: archives of the Metropolitan Opera, reference 4: Kutsch & Riemens

|