Roberto Romito was a fisherman in Naples; at least, that's the story as told by himself (although there is just enough sea in his native

Livorno, too, for a fisherman). It was, as the story goes, the managing director of the Boston Opera Company, Henry Russell, who discovered

Romito's singing talent. Next, Russell had his fisherman tenor learn to read and write, and then study music and voice (and languages) –

in Paris, which is another rather unlikely twist in the tale, but the tale is still Romito's own.

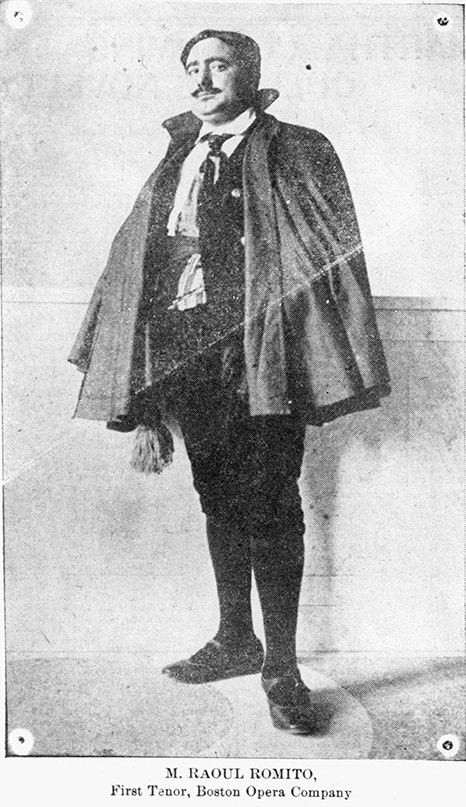

In any case, he made his debut at, right, the Boston Opera in 1912, at age 30, as Turiddu and with the new first name "Raoul", and was that

theater's first dramatic tenor. Not for very long, it would seem: there are many newspaper references to Romito's participation in the Boston

Opera's 1913 and 1914 post-season tours of New England, but I didn't find any reports on any Romito appearances at or with the Boston Opera,

or in opera at all. Perhaps it had to do with what the Boston Journal wrote: "If Signor Romito's acting were as fine as his voice, he would be

the superior of any tenor living. His voice is glorious."

Already in August 1913, Romito had appeared in vaudeville in New York City at the so-called Proctor's 5th Avenue Theater (which was located on

Broadway, in reality). In spring 1915, Romito sang operatic concerts with the touring Imperial Opera Company. On 6 September 1919, he took

part in a concert at Lewisohn Stadium in New York City together with Rosa and Carmela Ponselle. In September 1920, he was back on Broadway

and in vaudeville, singing opera and operetta selections at Strand Theater.

Other than that, he appears on American newspapers only with regard to his records: he was, from 1917 to 1931, a prolific recorder for

Columbia, Brunswick, Okeh and Victor. On disc, he sang exclusively songs – mostly no classic Neapolitan canzoni, but Italian songs of

the day for the large Italian expat community in the United States. Many of them seem to betray leftist inclinations; Romito recorded several

songs of the strong Italian anarchist movement, or an anticlerical satirical song for instance. But in between all that anarchist music, he

also recorded songs of clearly Fascist slant, including even the "Giovinezza" (the hymn of the Italian Fascist party). Politically weird as

that is, Romito's records made him very popular among Italo-Americans at his time.

Reference 1 and picture source: The Brattleboro Daily Reformer, 15 April 1913; reference 2: The Barre Daily Times, 21 April 1913;

reference 3: Rock Island Argus, 27 March 1915; reference 4: New York Tribune, 24 August 1913, 6 September 1919 and 20 September 1920;

reference 5: The Sun and The New York Herald, 12 September 1920; reference 6; Go Home