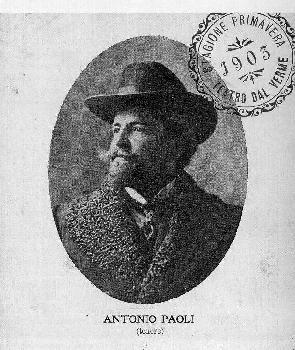

Antonio Paoli

14 April 1871 Ponce (Puerto Rico) – 24 August 1946 San Juan

In RA format

In RA format

In RA format

Paoli's parents were wealthy; his father was from Corsica, his mother from Venezuela. But a sugar price slump caused their bankruptcy, despair

and premature death, first of the father, then of the mother: at age 12, Antonio Paoli was an orphan. His sister Amalia took him to

Spain, where she lived and completed her vocal studies (she had already made her debut as a mezzosoprano back home in Puerto Rico) with financial

support by the Spanish queen herself. Coming of age, Antonio, too, studied voice. The Spanish queen paid for his tuition, as well, and sent him

to Milano in 1895. The same year and while still studying, he made his debut in Bari in Gounod's Polyeucte, under the name Ermogene

Imleghi Bascarán. (Don't be fooled by Kutsch & Riemens who think Imleghi Bascarán was his real and Paoli his stage name –

it's the other way round.)

In 1899, he made his debut at the Paris Opéra as Arnold, and it would seem that this was the first time he used his real name on stage;

at least, it has often been claimed that this was Paoli's first stage experience at all, which is of course not true (he is also documented to

have sung Edgardo in Valencia on 27 November 1897). A great career ensued. He sang in Florence, Venice (great success as

Manrico in 1903), Genova, Naples, Rome, at La Scala (where he was "primo tenore" from 1910), St. Petersburg, Moscow, Warsaw, Buenos Aires (where

he inaugurated the new Teatro Colón in 1908 as Radamès), Graz, Budapest, Cairo, and many other places. In 1902/03, he toured the

USA and Canada with a troupe directed by Pietro Mascagni. He toured the US again in 1920 (with the Chicago opera troupe) and in 1922/23 and

1926/27 (with the San Carlo Opera Company). Just the Metropolitan Opera never hired him (reportedly because Enrico Caruso was afraid of his

competition, which doesn't explain, though, why he didn't sing there after Caruso's 1921 death), and rumours about his sensational success as

Lohengrin at the Vienna Court Opera are just that, rumours: in fact, Paoli never sang in Vienna.

He sang primarily dramatic roles: Samson, Don José, Pollione, Chénier, Canio, Éléazar, Jean (Hérodiade),

Jean de Leyde, Vasco da Gama, Raoul, Rodrigue (Le Cid), Arnold, Manrico, Don Alvaro, Don Carlo, Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, Osaka, Poliuto

– and most important of all, Otello, his signature role.

1914 was a bad year for Paoli: he lost his voice, and as a consequence of mistaken investments also his entire fortune. He went to England and

sustained himself by – boxing!, which is probably a unique case in the history of opera singing. An injury put an end to his boxing career,

and in January 1917, against all odds, he made a comeback as Samson in Rome, and was most successful. In 1922, he moved back to Puerto Rico and

started to teach voice, but continued to sing at least until 1929, reportedly even until 1932 (the last few years only in Puerto Rico and Cuba).

In Puerto Rico, he mounted opera and zarzuela productions. Definitely the last time that he sang in public was at his sister Amalia's funeral in

1942.

Reference 1, reference 2, reference 3: Kutsch & Riemens, reference 4, reference 5

I wish to thank Thomas Silverbörg for the picture (top) and the recordings (Africaine, Aida).

I wish to thank Imogen Norcroft for the recording (Trovatore).

In 1997, a book was published on Antonio Paoli (it's still being sold via its own dedicated website):

Jesús M. López: Antonio Paoli, el león de Ponce

It is a large hard cover format with 921 pages. It reproduces 425 photos and documents. The paper quality is not too good, so the photos do not

come out too well. The text contains many reviews. It has a discography. The book had the potential to be a great book. BUT both the

chronology of his appearances is a disaster, besides many typos, which could have been overlooked if the chronology itself was not full of

errors. Thus it lists Paoli as having sung in places where it can be demonstrated that he did not sing (London, 1900) and that also his alleged

fellow interpreters cannot have sung with him, or where the theaters mentioned did not exist at the time of the performance. Cast information

is sometimes pure fantasy, certain artists being hundreds of miles away at the time they were supposed to be with Paoli. Numbers of

performances are even stranger. According to the book, Paoli is the only singer to have sung 43 times in a month in the same city (Graz, June

1904). What a wasted opportunity. Under no circumstances should this book be used to research other singers.

| Finally, a researcher living in Graz checked out, at the local

opera house, the number of performances of Paoli in Graz in 1904. After being asked, in an Argentinean Musical Journal, about Paoli's alleged 43

performances in one month, Mr. López claimed that it was a typo, and that the total number was actually 28 performances. Two things are

wrong with both numbers. First of all, the total of 43 was arrived at by adding the performances of single operas, as given by Mr. López,

that Paoli sang in Graz. So it could not be a typo in the first place. The number 28 was also improbable, since in places like Graz, the same

theater alternated opera and drama. The actual number of performances sung by Paoli in Graz in June 1904 is five. What can we conclude about

Mr. López' research abilities? Mr. López claimed he spent 20 years researching Paoli's appearances in all the places where Paoli

sang. Apparently, he missed Graz, like he missed Paris, London, Bourgogne (I never found that city on a map of France), Parma etc... What a

disservice to Paoli. The great tenor deserved better. |

|