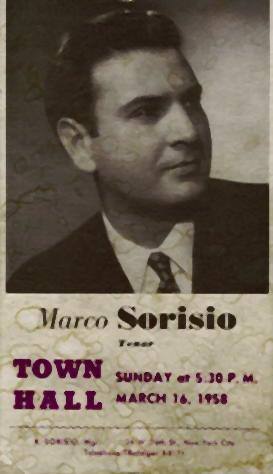

Ramon Marcos Sorisio was born in Mazatlán, Mexico, on February 11th, 1910. He died in Oakland, California on February 12th, 2000. He was the youngest son of a soap manufacturer. The family migrated to Oakland, CA in the mid 1920's. Sorisio studied in Oakland, and made there his opera debut as the First Armed Man in Die Zauberflöte, at the Scottish Rite Auditorium. In those days, Oakland was almost just as much of a cultural center as San Francisco, and renowned artists would make stops in both cities to give concerts. Marco would enthusiastically attend concerts of such greats as De Luca, Gigli, Schipa, Rosa Ponselle (he later sang with Camille Ponselle on one occasion), and many more. He was a big fan of Caruso, whom he knew only by his records of course. He sang in the San Francisco opera chorus under Gaetano Merola, who opened the War Memorial Opera House in 1932. In those days the company also traveled to Southern California, it performed in such places as the Hollywood Bowl. Maestro Merola was aware of Sorisio's latent talents, and years later told him, "Sei divenuto un artista consumato." In the late 1930's, he began to teach voice and, encouraged by the good response of the local public to his church singing, concerts, and operatic performances, he moved to Manhattan. There he continued to do what he did in California, throughout the greater New York area. Singing in various churches was very important to his livelihood, and this included a stint at a Synagogue, under cantor Rubin Tucker. A turning point in Sorisio's career came in the late 40's when he met Melchiorre Luise. The Neapolitan baritone, who had been promoted by Sol Hurok to perform basso comico roles at the Met and on tour, was present at a concert Sorisio was giving. Luise complimented him and offered to imitate his singing. Sorisio was delighted. Luise then proceeded to re-sing the same passage in his own way, and invited him to study with him. Sorisio was so impressed that he dropped everything, and spent the next few years reforming his technique under the strict guidance of Luise. His pupils became Luise's, who returned to Italy in 1950. Sorisio then resumed his singing and teaching careers. Among his pupils were Michael Kermoyan and Eugenio Fernandi (Luise's pupil in Italy). His voice took on more body and power maintaining, even improving his characteristic agility. Yet he was to become one of those fine singers who go relatively unnoticed. Though he never sang at the Met, or as a principal in any of the major houses, general manager Edward Johnson introduced him at a fund-raiser with the remark "We don't have all the good singers at the Met..." His brother, Roberto, bass-baritone, came to join him in the enterprise of Sorisio Concerts. They performed at Town Hall and other venues in New York, and in the San Francisco area. Later, Marco started a series of condensed operas at the Waldorf Astoria, where he performed and directed. Unfortunately, poor health curtailed his career as a leading tenor. As Stephen Zucker commented in his 80's magazine Opera Fanatic, "... he retired too soon." He moved back to Oakland and continued teaching and conducting opera workshops, from the 70's until his death at age 90.

Trying to understand how such a brilliant vocal artist would go so unrecognized, tenor Ross Halper conjectured that his career coincided with

an emphasis on the heavier Grand Opera repertory in the major opera houses, when his voice was more suited to Belcanto. Had he been active a

decade or two later, when a Belcanto revival began, he might have found his niche in the world of opera. One of his best roles was Rossini's

Almaviva, which he performed on tour well beyond the New York area. Melchiorre Luise said of his excellence in this role, "No one in Italy can

touch you as Almaviva!"

I would like to thank Ross Halper for the recording. I would like to thank Miguel J Fennick for the picture, and notes. |