The ancestors of Chilean singer Ramón Vinay came from the tiny hamlet of Larche, in France, 5 kilometers from the Italian border and 120

kilometers from Nice. His father, Jean Vinay Robert (1873–1950) emigrated very young to America, first to Mexico, then to Peru and

finally to Chile, where he arrived in 1898. He established himself in Chillán, a city 409 kilometers south of Santiago. There he became

a prosperous trader in leather horse saddles and harnesses, and there too he married, in 1907, a modest young seamstress, Rosa Elvira

Sepúlveda Lara (1887–1917). (Jean had married before, in 1900, another Chilean girl who died very young, in 1903, but gave him

his first son, Antonio.)

Ramón Mario Francisco Vinay Sepúlveda was born in Chillán on 31 August 1911, and was the third of four children.

In 1914, his father traveled to France to buy machinery for his workshop. The First World War caught him there and forced him to serve in the

French army. When he obtained a leave, in 1917, he deserted and returned to Chile to find that his wife had already died. In 1920, the French

government granted an amnesty for cases such as that of Jean Vinay, and he sold all his belongings in Chillán and took his children to

France. He established in Digne, where Ramón finished high school.

His father wanted him to study architecture, but he rather wanted to become a violinist. Therefore, in 1928, at 17 years old, Ramón Vinay

followed his in father's footsteps and left for Mexico, where he obtained employment with his grandmother's family, the Robert, in Mexico City.

He started very humbly, but soon he founded a company with his brother Otto and had his own cardboard boxes factory. He had not shown any

special interest in singing, but always used to sing at parties where his voice was noticed.

In about 1930, he started his singing studies with José Pierson (1861–1957). He was a very good teacher and contributed to the

development of a whole generation of Mexican singers: Alfonso Ortiz Tirado, Juan Arvizu, Pedro Vargas, Jorge Negrete and many others.

Though Ramón Vinay sang during this period of formation occasionally as a bass (his "Vecchia zimarra" was always a success), his  professional debut took place on 16 September 1931 at the Teatro de las Bellas Artes in Mexico City, in the

baritone role of Alphonse in La favorite.

professional debut took place on 16 September 1931 at the Teatro de las Bellas Artes in Mexico City, in the

baritone role of Alphonse in La favorite.

Some friends persuaded him to enter an amateur radio competition sponsored by Coca-Cola, and this was the beginning of his artistic life. For

several years he sang in Mexican radio broadcasts, where he was announced as "the great Mexican baritone".

In 1940 he married a Mexican girl, María de los Angeles Padilla Brondo. The couple had two children, Rosita Elvira and Ramón jr.

Ramón Vinay came back to the opera, at the Bellas Artes, still as a baritone, during the season 1938/39, singing in Aida and

La Gioconda. There is, at some point in 1939, a strange appearance of Ramón Vinay in New York. He appears on the roster of a

musical show by James McHugh and Al Dubin, Streets of Paris at the Broadhurst Theater. The show included such different stars as Carmen

Miranda, Jean Sablon, Yvonne Bouvier and Abbott & Costello. The next season 1939/40 saw him again in Aida, in Il trovatore and

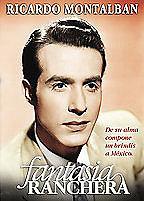

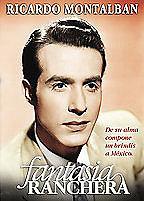

Tosca. In 1943 he appeared in a film, "Fantasía ranchera" sharing honours with several Mexican opera singers such as Josefina

Aguilar, Paco Zárate and Pedro Vargas and the very young actor  Ricardo Montalbán. Until January 1944, he continued singing baritone roles in Mexico, adding to his repertory

the title role in Rigoletto, Silvio in Pagliacci and Germont in La traviata.

Ricardo Montalbán. Until January 1944, he continued singing baritone roles in Mexico, adding to his repertory

the title role in Rigoletto, Silvio in Pagliacci and Germont in La traviata.

Five months after his last performance as a baritone (La favorite, 23 January 1944), he made his debut as a tenor, in nothing less than

the title role of Otello (from 19 June 1944) with Stella Roman as Desdemona and Frank Valentino and Carlo Morelli sharing the role of

Iago. "Musical America" reporting this event wrote that "the sensation of the season was Ramón Vinay's superb characterization of the

difficult title role in Verdi's Otello."  Next

year he was Samson, Cavaradossi, Don José and des Grieux (Manon Lescaut). Singing opposite him as Tosca was the American soprano

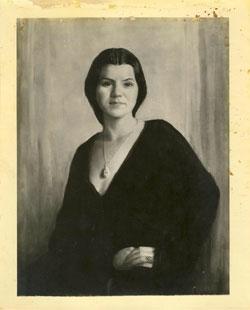

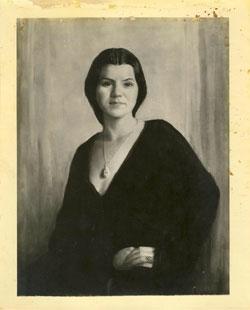

Lushanya Mobley (1906–1990), who later became his second wife. Some of the performances were conducted by Jean Paul Morel, who helped

Vinay to obtain his first contract outside Mexico.

Next

year he was Samson, Cavaradossi, Don José and des Grieux (Manon Lescaut). Singing opposite him as Tosca was the American soprano

Lushanya Mobley (1906–1990), who later became his second wife. Some of the performances were conducted by Jean Paul Morel, who helped

Vinay to obtain his first contract outside Mexico.

He made his debut at the New York City Center Opera on 30 September 1945 as Don José in Carmen, a role he sang several times

during October and November that year. His Don José attracted the attention of Edward Johnson, and Vinay got a contract to sing at the

Met.

His debut at the Metropolitan Opera took place on 22 February 1946, again in Carmen. "Vinay looked well and performed with musicianly

purpose, but the traces of baritone origin were still in his tones." "His voice is of good size and likeable quality; some tenseness in its

production may be attributable to the psychological strain of a debut in this theater. His singing gave the impression of color and of

effectiveness as an expressive vehicle, while his acting revealed unusual dramatic vigor and spontaineity" (Francis D. Perkins in the "New

York Herald Tribune").

The role of Don José became Vinay's "war horse" during that part of his career. He sang it in several important cities in the USA,

including a performance sung in English, on 9 July at the Hollywood Bowl, conducted by Leopold Stokowski.

He returned to Mexico to sing at the Bellas Artes in July and August, Aida, Carmen and Otello. He also had time to

shoot a second film, "Sinfonía de una vida", with tenor Luis G. Roldán and composer Miguel Lerdo de Tejada.

He sang his first Otello at the Metropolitan on 9 December 1946, replacing an ailing Torsten Ralf. The critic Louis Biancolli wrote in

the "New York World-Telegram": "A young Chilean tenor, Ramón Vinay, made Metropolitan history last night by stepping successfully in

the role of Verdi's Otello... on nine hours notice. What's more, Mr. Vinay went on without rehearsal in a part he had sung only once

before – in Mexico City two years ago... Here and there, Mr. Vinay's voice rebelled against the fearsome tessitura of the role. If one

or two notes went limp, the wonder was that more of them didn't. The point is that Mr. Vinay's performance was mainly sound, promising even

more in future hearings. There was nothing in last night's reading that one good rehearsal couldn't fix. The requisites for a fully acceptable

Otello were all there. It's now up to Ramón Vinay to prove the rest."

It was a good early account, indeed, for a singer who was going to become one of the leading Otellos of the century.

After several more performances at the Met (Aida, Carmen and Otello), he made his debut in Italy, on 3 September 1947 at

the Teatro della Pergola in Florence, in Otello with Onelia Fineschi and Tito Gobbi. He sang this opera and Pagliacci in Genoa,

Turin and Bologna. The Italian critic Giorgio Gualerzi commented that "he seemed a baritone or rather a bass contrasting with the clear

ringing baritone of Tagliabue... but after the third act, his dramatic efforts received the approval of the audience who granted him a well

deserved ovation at the end of the opera."

He had to return to the USA, called by Arturo Toscanini to sing Otello in the NBC broadcasts of that opera from Studio 8 in New York.

The first two acts were broadcast on 6 December, and the last two acts on 13 December. Sixty years later, it is still considered by many "THE"

unsurpassed and reference Otello. Critics such as Olin Downes (New York Times) greeted the evening as "not only the most beautiful

performance of Otello ever heard, but the best ever". Another critic described his performance as "the epitome of vocal artistry"

From New York he had to fly to Italy again, this time to Milan, where he inaugurated the opera season at La Scala on 26 December 1947 in

Otello with Maria Caniglia and Gino Bechi. The conductor was Victor De Sabata.

The year 1948 started with several concerts in Colorado and then performances of Pagliacci and Aida at the Metropolitan.

A critic wrote about his Radamès: "Mr. Vinay sang with dignity and authority... and is to be commended particularly for following Verdi's

directions and singing the final B flat of the aria pianissimo, rather than bellowing it forte as many tenors like to do." Vinay used to laugh

happily when remembering that review: "It would have been impossible for me to sing it the usual way..."

He added the role of Julien in Charpentier's Louise in Boston ("Vinay was a potent if vocally strained Julien"). Later that year,

he scored a great success at the Arena di Verona, singing Otello with Tebaldi and Carmen wih Nicolai.

He sang in Chile for the first time in September 1948, appearing at the Teatro Municipal in Santiago in Otello and Aida with

Caniglia and in Carmen with Fedora Barbieri; and on 29 November he inaugurated the opera season at the Metropolitan, with Otello.

That performance was the first time that an opera was telecast in New York.

In 1949, he sang his usual repertory in New York (Metropolitan), Naples (San Carlo), Milan (Scala) as well as on the coast-to-coast

Metropolitan tour. Later that year he resumed the opera Samson et Dalila (which he had sung earlier in his tenor career, in 1945 in

Mexico and in 1947 in Cincinnati), interpreting it at the Metropolitan, La Scala and the Terme di Caracalla in Rome.

In 1950 he made his debut at Covent Garden in London singing Otello with Tebaldi and Bechi, as a member of the La Scala Touring

Company. The critic of "The Times" wrote: "The Chilean tenor, Ramón Vinay, had no Italian ring in his tones which were closed, though

not, however, tight, for he sang on the note and in tune. His fine presence and the excellent use he made of his voice enabled him easily to

dominate the stage when he was on it."

In October he sang his first Wagnerian role, Tristan in San Francisco with the renowned Kirsten Flagstad as Isolde under the direction of

Jonel Perlea. Later that season, he sang the role in New York opposite Helen Traubel under Fritz Reiner. "Mr. Vinay's Tristan revealed his

power as a singing actor far more profoundly than anything else he has done here... His German diction was still somewhat Latin, but he knew

what he was singing about every moment. His Tristan was noble, courtly, passionate and metaphysically subtle, by turns. He made the anguish

of the dying knight in the third act almost unbearably keen", wrote one New York critic.

In 1951 he sang at La Scala the role of Griscka in La leggenda della città invisibile di Kitesc (nothing else than the Italian

version of Skazanie o nevidimom grade Kitezhe i deve Fevronii by Rimskij-Korsakov). During that year, he sang his usual warhorses

(Otello, Carmen, Pagliacci) throughout the United States, as well as in Salzburg, Santiago and Lima.

In summer 1952, he was invited to sing for the first time in Bayreuth, Tristan und Isolde conducted by Herbert von Karajan. Sir Harold

Rosenthal wrote in "Opera" that "his Tristan was noble and poetical, but hardly real". Other Wagnerian roles followed successfully. My late

friend Uwe Schweikert wrote me a letter from Stuttgart in April 1987, on Parsifal: "I vividly remember the tremendous impact Vinay made

on me, in the second act. He was so impassioned (as was Mödl), that he was barely audible and voiceless in the last act." He would sing in

Bayreuth for six seasons.

Also in 1952, he sang for the first time the title role in Lohengrin, at the Murat Theater in Indianapolis. The cast included the

mezzosoprano Blanche Thebom as Ortrud and the conductor Fabien Sebitzky. It was a concert version and sung in English. As far as we know, those

two performances on 23 and 24 February, plus two other in Pittsburgh in 1954, with Eleanor Steber as Elsa, were the only ones as Lohengrin that

he sang in his career. In 1952, he also sang Otello again in Salzburg and returned to Chile to sing Don José, Otello and Samson.

In 1953, he sang for the first time at the Teatro dell'Opera in Rome, as well as in Palermo, Lisbon, Amsterdam, Bayreuth (Parsifal,

Walküre and Tristan und Isolde), Rio de Janeiro and London (Walküre). His first German role at Covent Garden

was well received: "Mr. Ramón Vinay when he appeared before at Covent Garden sang Otello. He is a true heroic tenor without German

throatiness but quite at home in Geman music. His voice has character and his stage demeanour is natural." (The Times, 20 October 1953)

In 1954 he started, slowly, to increase his German repertoire, leaving out some of his Italian/French operas. He sang his first

Tannhäuser at the Metropolitan and then, at La Scala, the main role in Cyrano di Bergerac by Franco Alfano and Aegisth in Strauss'

Elektra. In the 1954/55 season at the Met, he added the role of Herodes in Strauss' Salome.

During 1955 he was heard as Siegmund, Parsifal, Tannhäuser, Herodes and Cyrano, and also as Otello and Samson. The revival of

Otello at Covent Garden was especially well received: "Mr. Vinay is a a powerful actor too, his voice is heroic, though more like a

German than an Italian tenor, and it is lacking in variety and the subtler inflections, yet he sustained the part admirably, conveying the

impression with increasing force that Otello is half mad, in the grip of a compulsion neurosis." (The Times, 18 October 1955)

An unusual role for Vinay was on his schedule at the 1955 Holland Festival in Amsterdam, Lenskij in Evgenij Onegin. Rosenthal wrote in

"Opera" (June 1958): "His dramatic insight is such that he was able to create a most moving figure of this character, and Lensky's emotional

crisis in the Ball Room scene was, on that occasion, entirely credible. The beautiful aria allotted to the tenor before the duel scene as sung

by Vinay was one of those rare and treasured moments in my opera-going."

In September 1956 he sang in Chile for the last time as a tenor, in Otello, Carmen and Pagliacci. He added a new tenor

role to his repertory in 1956 when he sang for the first and last time in his life the role of Avito in L'amore dei tre re by

Montemezzi, in Philadelphia. From 1957, he sang namely German roles: Loge, Siegmund, Siegfried, Tristan, Parsifal. His Tristan at Covent

Garden on 4 June 1958 did not impress the critic of "The Times":

"Mr. Vinay's voice is destitute of ring. In Otello he made up for the lightness of his singing by clever histrionics. He did something of the

sort with Tristan's monologue in the third act, but Tristan is not susceptible of the dramatic treatment possible to the Moor of Venice."

The single exception was Otello, an opera that he sang for the last time in 1959, in several cities in France. He sang his last tenor

role (Herodes) at the Metropolitan, in March 1962.

Just for the purpose of statistics, Ramón Vinay sang at the Metropolitan Opera House in 17 seasons, 15 roles in 15 operas, in a total

of 169 performances between 22 February 1946 and 31 March 1966, 123 in New York and 46 on tour.

Sir Rudolf Bing wrote in his autobiography "5000 nights at the opera": "The individual performance I remember best was that of Ramón

Vinay as Otello; it was the two hundredth time he had sung the role, and never in my life have I heard it sung and acted so perfectly." Bing

also gives us a good summary of the so-called "Three Tristans Performance" in the 1959/60 season at the Metropolitan: "...I found myself

without a Tristan to partner her third Isolde (Birgit Nilsson). Ramón Vinay had been scheduled, but was having vocal difficulties; he

had barely made it through the previous performance, and simply did not feel well enough to undertake this killing role after only four days'

rest." Unfortunately the covers, Karl Liebl and Albert Da Costa, also had catched cold (it was New York in December) but "...in order not to

disappoint (the audience) these gallant gentlemen, against their doctors' orders, agreed to do one act each... fortunately, the work has only

three acts."

In the wonderful book "The last prima donnas" by Lanfranco Rasponi (New York, 1984), some great artists of the past commented about Vinay, the

singer:

"Ramón Vinay was a superb singing actor, but the voice was somewhat veiled." (Renata Tebaldi)

"For many seasons my partner was invariably Ramón Vinay, whose voice was opaque and strangely veiled but who always brought out a

living character." (Elena Nicolai)

"Vinay's instrument was what it was, always slightly veiled, but his intensity was galvanizing, and I enjoyed very much appearing with him as

Dalila too." (Gianna Pederzini)

He returned to the baritone clef and in July 1962 sang the role of Telramund in Lohengrin at the Bayreuth Festival. In November 1962, he

sang Iago to the Otello of Mario Del Monaco, in Dallas. Rual Askew wrote in "Opera" (February 1963):

"Vinay was magnificently malevolent in action and superbly musical in his characterization, even though the voice is really too light for the

weight we prefer."

A second career looked promising, and he sang Scarpia, Iago, the Holländer, Nerone (L'incoronazione di Poppea), Germont, Amonasro,

Dr. Schön (Lulu), Falstaff, Gianni Schicchi, Michele (Il tabarro), Escamillo, Belcore, Kurwenal, Marcello (La

bohème) and Tonio (Pagliacci). He also sang a few bass roles, but to tell the truth without much success: Don Bartolo (Il

barbiere di Siviglia: "...not only was his voice gone, he was a flop as a comedian"; "the sound was dry, the action unfunny"), Varlaam

(Boris Godunov), Don Bartolo (Le nozze di Figaro), Wotan (Das Rheingold), Commendatore (Don Giovanni), Pizarro

(Fidelio) and Grande Inquisitore (Don Carlo). He sang two new baritone roles: Le mari in C'est la guerre, a one-act opera

by Emil Petrovics, in Nice (1965), and Prospero in Der Sturm, a three-act opera by Frank Martin, in Geneva (1967).

He sang at the Teatro Municipal in Santiago, for the last time in opera, in September 1969 as Scarpia and Iago. The evening of September 22nd

was full of emotion.

It was Vinay's farewell to opera. He sang the first two acts of Otello as a baritone, and in the last act the title role, as a tenor.

The British "Opera" magazine (December 1969) wrote: "It is very difficult to describe the last moments of Vinay's singing career on the stage

of the Teatro Municipal. Many in the audience felt that time had stood still, because Vinay was in really superb form. Emotion mounted when

all the singers of the company, the chorus and the staff paid their own homage to the singer. The National Anthem resounded, while a shower of

rose petals invaded the stage and little Chilean flags were in the hands of everyone in the audience. A silver tray was presented to Vinay. It

had an inscription containing some of the last lines of Otello: 'Ecco la fine del mio cammin... O gloria... Otello fu...'"

Vinay sang however still a few more baritone performances in Portland and Cleveland, and then in a concert in Santiago at the Teatro Gran

Palace in 1971. The last time he sang in Chile was in March 1974 in a number of recitals in different cities.

Ramón Vinay was a "character" on stage and in private life. Though he married in 1940 in Mexico, he soon fell in love with another

woman. In 1945 he sang Tosca with the soprano Lushanya Mobley, a lady announced as "an Indian princess of the

Chickasaw tribe". Vinay left wife and children and started a new life with his soprano. Vinay was a womanizer. He declared, on more than one

occasion, that his greatest passions were food and women (and I should add, drinking too). When a journalist asked him his opinion about women,

the answer was: "Ah! the most divine of passions!!"

Regarding his opera characters, he declared in 1958 in Radio Barcelona:

"I am the best paid murderer in the world (Don José, Canio, Otello) but I enjoy more singing Samson because instead of a single murder

like in Otello or Pagliacci, I kill a great number of Philistines in the temple. But to tell the truth, it is very bad business

because I'm paid the same."

In the early '70s Ramón Vinay's multi-faceted career expanded into another direction. Facing retirement as a singer, he began to assert

himself as a stage director. He mounted highly-praised productions of Otello, Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci for the

Portland Opera, where he also participated singing the roles of Iago and Tonio. In 1971, he was appointed artistic director of the Teatro

Municipal in Santiago de Chile. Because of political complications, however, the announced opera seasons had to be cancelled.

Vinay earned a fortune when he was at the top, and lost it in ill-advised investments. He bought in France, 120 kilometers south from Paris,

the chateau Changy-les-Bois. It was a historical castle, a monument from the XVII century but altered in times of Napoleon. He intended to

rest there from his musical activities, and installed a poultry business. It was a total failure and he lost more than thirty thousand dollars

in that experiment. Though he had bought the castle very cheap, to maintain it meant to invest a fortune, and after ten years he decided to

sell it and to move to Spain.

Vinay declared in an interview in Cleveland that "an artist must suffer, not just because he can sing, but because he was born to be an

artist". And then, "this life, this profession gives you a chance to meet so many people, visit so many countries, learn so many languages...

but for 40 years, I have not had time to learn to play bridge or golf. And now for the first time, I feel very homesick for my Spain."

Describing the origin of his passionate love for Spain, Vinay said that he had never even visited his adopted country until 15 years

ago. Then, during a leisurely motor trip (in 1957), he accidentally ran accross the place of his dreams – "a deserted spot on the

coast where the mountains rise from the sea"... and within a few days, the singer had purchased 1500 feet of ocean-front property. And before

long, he had sold his chateau in France, gotten rid of his apartments in Milan and New York, packed his belongings in 60 or 70 trunks and

shipped everything to his new home in Benisa, Alicante, where, he said, he lived "like Onassis".

In the book "Opera stars in the sun" by Mary Jane Matz (New York, 1955), Ramón Vinay spoke of his hobbies: photography, astronomy,

high-fidelity equipment and carpentry. "A high C seems very unimportant when you are busy studying the sky." Manual work was

his greatest release from the tensions of his musical tasks, but he cautioned not to become too involved: "Then a hobby becomes a task and is

not fun anymore."

After a long illness, Lushanya Mobley died in 1990. Her family took possession of Vinay's entire fortune, and he was declared mentally

disabled and sent to sanatoria in the United States, where ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) was applied, affecting his already weak mind and

body.

The children from his first marriage rescued him and took him to Mexico, first to Guadalajara and then to Puebla, where he died of a

heart attack on 4 January 1996. He was 84 years old. The Chilean government took his remains to Santiago, where he received

official honours at the Teatro Municipal, and then to Chillán, where he was buried in the local cemetery.

His grave is close to that of the great Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau.

A biography of the artist was published one year after his death, in January 1997:

"Ramón Vinay: De Chillán a la gloria" by Carlos Bastías and Juan Dzazópulos (in Spanish).

Juan Dzazópulos, 2010

professional debut took place on 16 September 1931 at the Teatro de las Bellas Artes in Mexico City, in the

baritone role of Alphonse in La favorite.

professional debut took place on 16 September 1931 at the Teatro de las Bellas Artes in Mexico City, in the

baritone role of Alphonse in La favorite. Ricardo Montalbán. Until January 1944, he continued singing baritone roles in Mexico, adding to his repertory

the title role in Rigoletto, Silvio in Pagliacci and Germont in La traviata.

Ricardo Montalbán. Until January 1944, he continued singing baritone roles in Mexico, adding to his repertory

the title role in Rigoletto, Silvio in Pagliacci and Germont in La traviata.  Next

year he was Samson, Cavaradossi, Don José and des Grieux (Manon Lescaut). Singing opposite him as Tosca was the American soprano

Lushanya Mobley (1906–1990), who later became his second wife. Some of the performances were conducted by Jean Paul Morel, who helped

Vinay to obtain his first contract outside Mexico.

Next

year he was Samson, Cavaradossi, Don José and des Grieux (Manon Lescaut). Singing opposite him as Tosca was the American soprano

Lushanya Mobley (1906–1990), who later became his second wife. Some of the performances were conducted by Jean Paul Morel, who helped

Vinay to obtain his first contract outside Mexico.