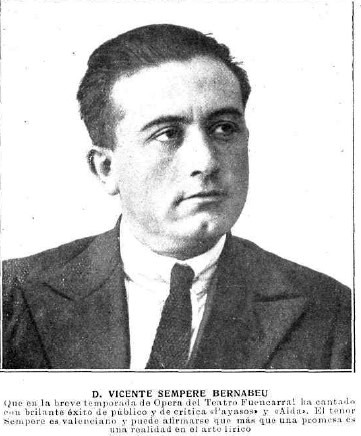

Vicente Sempere

Sempere studied with Lorenzo Simonetti first, then with Concepción Callao in Barcelona. He

made his debut in Mataró in Marina by Arrieta (no date known).

In the 1920s, he was a successful opera singer both nationally and internationally. Always an important figure in the musical life of Valencia,

he sang both at the Teatro de la Princesa (Calaf, 1929) and the Teatro Principal (his birthplace Onil is in the province of Valencia). He also

sang at the Teatro de la Zarzuela in Madrid (Hoffmann, 1928) as well as in Milano, Rome, New York or Buenos Aires – unfortunately, no

precise theaters or concert venues are ever given anywhere (he did not sing at the Met or the Teatro dell'Opera in Rome, for sure), nor dates

or roles. In any case, he was particularly renowned as Lohengrin and Enzo Grimaldo.

In the 1930s, he turned to zarzuela: Jugar con fuego, La tempestad, La bruja, Los de Aragón or Los

claveles, at theaters like the Apolo or the Reina Victoria, both in Madrid. With the troupe of composer José Serrano, he toured all

of Spain.

The big break in Sempere's life came when the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936. He obviously stopped singing – for good, as it would

turn out. Already before, he had engaged in politics and was an official of the party "Izquierda Republicana" (Republican Left) in the

province of Valencia. After the outbreak of the war, he assumed the nom de guerre "Morralla", and worked as a prison guard for the Republicans (i. e. the mostly left-wing opponents of

Franco and his fascist movement).

In March 1939, the Civil War was practically over, and Franco had won it. Only Alicante was still free (it fell on 30 March), and on 28 March,

a multitude of desperate Republicans hoping to escape from Spain gathered in the port of the city. A British merchant ship, the SS Stanbrook,

was loading oranges, and the only hope of the Spanish anti-fascists to leave before Franco's troops arrived. The captain, Archibald Douglas,

made the heroic decision to disobey the orders of the ship owner not to allow any refugees on board, and on the contrary, took all of them:

2638 people! Vicente Sempere was registered as passenger no. 2628. Heavily overloaded with people and oranges, chased by the

victorious Spanish fascists (and at one critical moment protected by a Royal Navy ship), the Stanbrook actually managed to deliver all her

refugees to Oran in (then French) Algeria.

Unfortunately, the French government was more than eager not to enrage Francisco Franco, and interned the male refugees in forced labor camps,

where they had, for instance, to build the Trans-Saharan Railway. The dire conditions under which they lived and worked only worsened when the

Nazi puppet regime harbored in Vichy took France over, and the Spaniards remained prisoners and forced laborers through the end of WWII, which

in North Africa arrived in winter 1942/43, when American and British forces liberated the region, and the Spanish Republicans. Vicente Sempere

is mentioned in several accounts of other Spanish prisoners; for instance, when he was interned in the notorious Bou-Arfa camp, the inmates

organized a Valencian cultural event, and Sempere sang a song in Valencian dialect, and altered the text in "I shit on all Frenchmen".

Fortunately, none of the guards understood any Valencian...

In Spain, the Franco regime investigated against Sempere, though not in an unbecoming hurry – by 1964, they were still unsure what

exactly he had done (in their terminology: which crimes he had committed) in the Civil War. And at that time, he still lived abroad!!, though

I could not find out where. Obviously, the (hesitant) amnesties that the Franco government granted in the 1960s to former Civil War opponents

eventually included also Sempere; as he had long ceased to be a person of public interest, all details lie dormant in Spanish archives, but he

was the object of repeated administrative and judiciary communication in the 1960s, and must have been allowed to return, eventually, since he

died in Alicante in 1974.

Reference 1; reference 2; reference 3: Arte y Patrimonio no. 1/2016; reference 4 and picture source (bottom); reference 5/a>; reference 6;

reference 7; reference

8; reference 9 and picture source (top); reference 10: El Pueblo, 26 March

1931; reference 11

I would like to thank Thomas Silverbörg for the recording. |