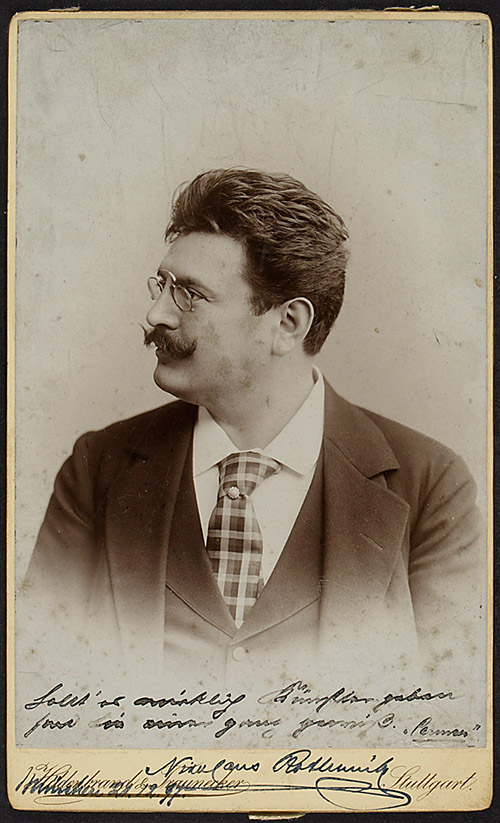

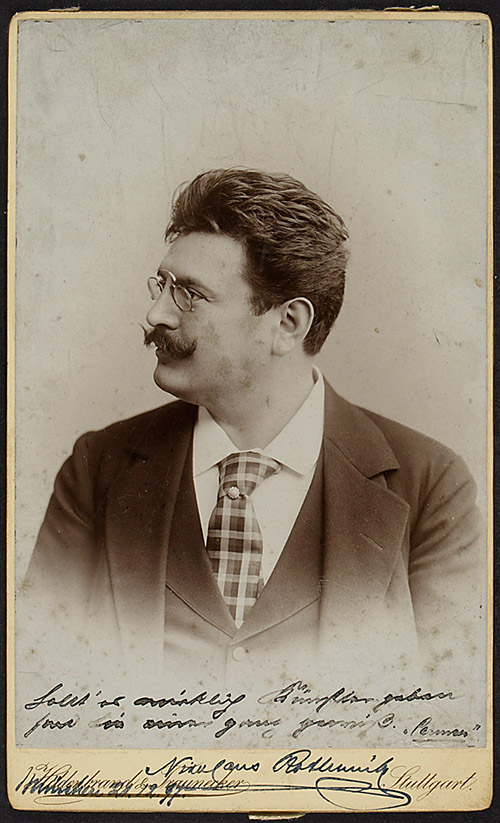

Nikolaus Rothmühl

24 March 1857 Warsaw – 24 May 1926 Berlin

Born Nachman Rothmühl, he was the son of a well-off Jewish factory owner. His father wanted him to take over the

company, and thus strongly opposed his plans of becoming an opera singer. But his wife and the cantor of their synagogue convinced

him to let Nachman take voice lessons, and they found him one of the most famous voice teachers of the period: Joseph Gänsbacher

in Vienna.

Gänsbacher accepted Rothmühl, although the young man spoke no German at all; but while his language skills improved rapidly,

progress in singing was slow, and Gänsbacher was dissatisfied for a while. But then, rapid improvement set in on the vocal front,

as well, and after three (instead of the envisioned six) years of training, Gänsbacher declared Rothmühl ready for the

stage.

He made his debut as Cossé in Les huguenots in 1881 at the Vienna Hofoper, where he didn't get to sing any important parts,

though. In 1882, he made guest appearances in Dresden and at the Berlin Hofoper, and was so successful that both theaters wanted to

hire him; he chose Berlin. He had a gleaming, easy top, and enormous versatility; he sang Vasco da Gama, Riccardo, Belmonte, Tamino,

Fra Diavolo, Raoul, Tannhäuser, Siegmund, Éléazar, Canio, Florestan, Radamès, Guglielmo Ratcliff, Masaniello... and

had glorious success in all those roles and styles. His noble musicality was as much lauded as his acting abilities. Just his Stolzing

and his Lohengrin got chilly reviews. However, in the early 1890s, both the soprano Bertha Pierson (the wife of Hofoper director

Henry Pierson) and heldentenor Eloi Sylva intrigued against Rothmühl, he lost

some of his roles and didn't get to sing others, and in 1893 he left Berlin.

He toured the Netherlands and Sweden, and then joined Walter Damrosch's German Opera Company that staged Wagner at the New York Met,

with excellent casts. Rothmühl sang Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, Siegmund and Stolzing, and – somewhat surprisingly –

Siegfried in Götterdämmerung. Damrosch's company had enormous success (the Met never again let them their theater),

and that way, Rothmühl became famous as a Wagner tenor in America. Damrosch continued to stage his Wagner performances at the

Brooklyn Academy of Music. On 23 March 1895, Rothmühl bid farewell to New York with a concert performance of Parsifal at

Carnegie Hall.

He returned to Germany, and became a member of the Stuttgart opera, where he sang Raoul, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, Siegmund, Otello.

In 1899, he was also back to Berlin; not at the Hofoper (where Pierson still reigned), but at the Theater des Westens: Éléazar,

Fra Diavolo, Florestan. The audience enthusiastically welcomed him back. In 1901, he left Stuttgart over a quarrel with the theater

management. His health began to fail; guest appearances in Basel were utterly unsuccessful. He fared better in Cologne.

Still in 1901, he became professor of chant and acting at the Sternsches Konservatorium in Berlin, where he taught very successfully

until 1925. He sang on smaller Berlin stages (Theater des Westens, Nationaltheater, Morwitz-Oper) until 1905 or 1907, depending on

sources. He is thought to never have recorded, but let's see what we'll think by the end of this page...

Reference 1: Einhard Luther, So viel der Helden. Biographie eines Stimmfaches Teil 3, Berlin 2006; reference 2: Kutsch &

Riemens

Picture source: Theatermuseum Wien

What comes now is my wildest speculation so far on Historical Tenors, but a fascinating and not entirely unfounded one.

François Nouvion, the founder of this website, had a very elusive record in his collection, on the (always elusive) Elephone

label, which was the export label of the German Lyrophon company: on one side, Asile héréditaire, in German,

sung by Selmar Cerini, although the label says by "Lewandowski"; on the other side,

Winterstürme, sung by (as per label indication) "H. Pietsch". While Cerini is easily recognizable, nobody seems to know

the voice of "H. Pietsch". In any case, it's definitely not Martin Pietsch, a

third-rate Brno operetta tenor who sang on Lyrophon, as well. "H. Pietsch" is a singer with great stylistic authority, and very

profound technique, although the voice is somewhat worn, which means that he cannot have been young when making this recording. But

nobody has ever been able to find any other tenor called Pietsch and active in Germany around or shortly after 1900.

Christian Zwarg, the fantastic Berlin sound engineer and voice expert, said when first hearing the "H. Pietsch" Winterstürme

record, that in his opinion, the singer's style seems to reveal a 19th century schooling, without the "Sprechgesang" so beloved of the

Bayreuth style of the early 1900s, and that singer must have been born in the 1860s or even earlier. Zwarg later changed his opinion

and said "H. Pietsch" must have been Jean Nadolovitch, which certainly

proves an excellent ear as the timbres of the two singers are similar; and yet it isn't Nadolovitch, since the differences in both

vocal technique and subtleties of the respective accents when singing German exclude that possibility, and I'm still convinced that

Zwarg's spontaneous reaction was spot-on.

Zwarg's initial assumption was that the singer names on both labels (Lewandowski and Pietsch, respectively) were wrong by mistake;

quite logical if you know how Lyrophon worked – their labels are just as often wrong as correct; for instance, they always had

one recording of a given aria in their catalogue, and always under the same matrix number, but definitely not always the same

recording: when a matrix was worn, they would make a new recording of the same selection under the same number, but often with a

different singer. And to make things worse, if there were still labels with the name of the previous singer left, they would use them

also on records with the new recording, and only print labels with the new singer's name when the old ones were finished, which is

probably unique in the history of record companies...

However, in this particular case, the assumption was wrong. Years after Zwarg and Axel Weggen and I had tried to figure out who "H. Pietsch"

may have really been, a second copy of the record in question turned up, this time on Lyrophon – and with the same

label indications, "Lewandowski" and "H. Pietsch". So no mistake, but wrong names on purpose. Later again, Axel Weggen found

another "H. Pietsch" Lyrophon disc, Questa o quella – by the same singer as in Winterstürme, no doubt.

So this gentleman wanted to stay anonymous and hided behind the non-descript pseudonym "H. Pietsch". (By the way, someone came up with

the idea that "H." could be "Herr", like in "Mr. Pietsch". However, Herr is never abbreviated "H.", but "Hr.", and "H." can only be

meant to abbreviate some first name like Heinrich, Harald or Helmut. I think it was just chosen so as to make clear that the really

existing Martin Pietsch had nothing to do with it.)

I resorted to the strenuous but rewarding task of browsing all volumes of Einhard Luther's "biography of the heldentenor"; after all,

Luther details the careers of literally every single tenor who sang Wagner anywhere in Germany until 1918, so our tenor (obviously a

veteran Siegmund, and recorded in Berlin) must be in those books. His German is fantastic, but not native; he displays a

very slight accent that may be Yiddish or Polish (it's too slight to decide with utmost certainty). For instance, he sings

"weit geäffnet" instead of "weit geöffnet", and also a handful of other vowels irritate a little bit (the "u" in "Bruder" or

in "und Lenz", the "ei" in "vereint"). He is also a surprisingly lyrical, belcanto Wagnerian; the voice is so extremely beautifully

produced that for modern listeners, it seems almost incongruous in Wagner (of course, it wasn't incongruous before the belting style

developed in Cosima's Bayreuth had its way, cf. Winkelmann or Wallnöfer). His accent is far more obvious in the Rigoletto selection, where

he is perhaps less at home, although he masters the style excellently and sings a fantastic embellishment at the end; but his German

is certainly farer from native than in the Walküre selection: "lEUchtend umschweben", "soll nie EIne schÖNe", "fir keine

allein" instead of "für keine allein", "verschöner das Leben" instead of "verschönert das Leben", "mich HEUte

entzücken", "die and're erfrEUen" (twice), "im lästigen Banden" instead of "in lästigen Banden", "ihrer EiFERsucht kann

ich nur laCHen", "der Sieg, er blEIbt".

So we are looking for a singer born in the 1860s or earlier, an expert Siegmund but no really heavy tenor, with excellent German skills

but no native German speaker, and active in Germany. The only one in Luther's books that fits the bill is Rothmühl.

That may, however, not seem sufficient to actually ascribe those two recordings to him, so let's check the practicalities.

Rothmühl, at the time of the recordings (1905 or so), lived in Berlin and still performed every now and then, particularly also

Siegmund (one of his most famous parts); Lyrophon was based in Berlin. Lyrophon's owner was basso Adolf Lieban, whose brother, the

famous comprimario tenor Julius Lieban, was born in 1857 like Rothmühl,

and studied voice with Joseph Gänsbacher in Vienna like Rothmühl; it's very improbable that the two tenors did not know each

other. And Rothmühl was, in 1905 or 1906, clearly past his prime. My theory is that he did the Liebans the favor to record on

Lyrophon, but didn't want to be remembered, with his resounding name, in his then state of voice. (He didn't know the tenors of 100 or

120 years later, or he would have gladly signed with his name; what he was able to achieve past his prime is so much more than modern

singers at their peak do.)

So with all due caution, and stressing that there is no proof at all for my theory, I'm nonetheless convinced that in the "H. Pietsch"

recordings, we hear Nikolaus Rothmühl sing, unless anyone proves me wrong.

Many thanks to Axel Weggen for the recordings, to Christian Zwarg for their fantastic transfers, and to both of them for the long and

interesting discussions about "H. Pietsch".

|